HISTORY SCHOOL BASED ASSESSMENT EXEMPLARS - CAPS GRADE 12 TEACHER'S GUIDE

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY

SCHOOL BASED ASSESSMENT EXEMPLARS - CAPS

GRADE 12

TEACHER GUIDE

Guidelines for Learners and Teachers: Exemplar Responses

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | PAGE | |

| 1 | Introduction | 3 |

| 2 | Aims and Objectives of School-based Assessment | 4 |

| 3 | Assessment Tasks as outlined in the CAPS | 5 |

| 4 | Programme of Assessment and Weighting of Tasks | 6 |

| 5 | Quality-assurance Process Followed | 7 |

| 6 | Assessment Tasks: Source-based Questions | 19 |

| 7 | Guidelines for learners and Teachers: Exempler Responses | 40 |

| 8 | Marking Guidelines and Rubric | 66 |

| 9 | Bibliography | 88 |

1. INTRODUCTION

Assessment is a continuous, planned process of identifying, gathering and interpreting information about the performance of learners, using various forms of assessment. It involves four steps: generating and collecting evidence of achievement; evaluating this evidence; recording the findings; and using this information to understand and assist with the learners’ academic development. Assessment should be both informal (assessment for learning) and formal (assessment of learning). In both cases regular feedback should be provided to learners to enhance the learning experience.

School-based assessment (SBA) is a purposive collection of learners’ work that tells the story of their efforts, progress or achievement in a given area. The quality of SBA tasks is integral to learners’ preparation for the final examinations. This booklet serves as a resource of exemplar SBA tasks to schools and subject teachers of History. SBA marks are formally recorded by the teacher, for progression and certification purposes. The SBA component is compulsory for all learners. Learners who cannot comply with the requirements specified according to the policy may not be eligible to enter for the subject in the final examination.

The formal assessment tasks provide you with a systematic way of evaluating how well learners are progressing. The booklet contains information on how to undertake research assignments, source-based tasks and essay questions. Formal assessment tasks form part of a year-long formal programme of assessment. These tasks should not be taken lightly and learners should be encouraged to submit their best possible efforts for final assessment.

The educators are expected to ensure that assessment tasks are relevant and suitable to the context in which learners are being taught. However, all SBA should be aligned to the requirements prescribed in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) document.

This publication comprises four tasks that address the demands of the Grade 12 History curriculum. It is expected that these tasks will serve as a valuable resource for:

- History teachers, in providing examples of the types and standard of school-based assessment tasks that would be appropriate for their learners;

- Grade 12 History learners, in providing material that will assist them in their preparation for National Senior Certificate examinations in History.

2. AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF SCHOOL-BASED ASSESSMENT

- School-based assessment serves to provide a more balanced and trustworthy assessment system because it includes a greater range of diverse assessment tasks than is possible in external examinations.

- The exemplar tasks are aimed at reflecting the depth of the curriculum content appropriate for Grade 12.

- It reflects the desired weighting of the cognitive demands as per Bloom’s revised taxonomy: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating.

- School-based assessment improves the validity of assessment by including aspects that cannot be assessed in formal examination settings.

- It improves the reliability of assessment because judgments are based on many observations of the student over an extended period of time.

- It has a beneficial effect on teaching and learning, not only in relation to the critical analysis and evaluation of History information and creative problem-solving, but also on teaching and assessment practices.

- It empowers teachers to become part of the assessment process and enhances collaboration and sharing of expertise within and across schools.

- It has a professional development function, building up teachers’ skills in assessment practices which can then be transferred to other areas of the curriculum.

- The tasks focus on the prescribed content as contained in the Curriculum and Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) effective from 2014.

The distinctive characteristics of SBA (and its strengths as one relatively small component of a coherent assessment system) have implications for its design and implementation, in particular the nature of the assessment tasks and role of the teachers’ standardisation procedures. These implications are summarised as follows:

- The assessment process should be linked to and be a logical outcome of the normal teaching programme, as teaching, learning and assessment should be complementary parts of the whole educational experience (i.e. the SBA component is not a separate one-off activity that can be timetabled or prepared for as if it were a separate element of the curriculum).

- The assessment process should provide a richer picture of what learners can do than that provided by the external examination by taking more samples over a longer period of time and by more closely approximating real-life and low-stress conditions (i.e. the SBA component is not a one-off activity done under pseudo-exam conditions by unfamiliar assessors).

- The formative/summative distinction exists in SBA, but is much less rigid and fixed than in a testing culture, i.e. learners should receive constructive feedback and have opportunities to ask questions about specific aspects of their progress after each planned SBA assessment activity, which both enhance History skills and help learners prepare for the final external examination (i.e. the SBA component is not a purely summative assessment).

- The SBA process, to be effective, has to be highly contextualised, dialogic and sensitive to learners’ needs; i.e., the SBA component is not and cannot be treated as identical to an external exam in which texts, tasks and task conditions are totally standardised and all contextual variables controlled. To attempt to do so would be to negate the very rationale for SBA. Hence schools and teachers must be granted a certain degree of trust and autonomy in the design, implementation and specific timing of the assessment tasks. However, every effort must be made to comply with the Programme of Assessment as contained in CAPS.

Teachers should ensure that learners understand the assessment criteria and their relevance for self- and peer assessment. Teachers should also have used these criteria for informal assessment and teaching purposes before they conduct any formal assessment so that they are familiar with the criteria and the assessment process.

The project provides exemplar tasks that are aimed at:

- Reflecting the depth of History curriculum content appropriate for Grade 12

- Reflecting the desired cognitive demands as per Bloom’s revised taxonomy: remembering, understanding, applying, analysing, evaluating and creating;

- Containing questions and sub-questions that reflect appropriate degrees of challenge: easy, medium and difficult

- Focusing on the content of the National Curriculum Statement (NCS) effective in 2013 and contain exposure to certain aspects of new content of the Curriculum & Assessment Policy Statement (CAPS) effective from 2014

3. ASSESSMENT TASKS AS OUTLINED IN CAPS

The final Grade 12 mark is calculated from the National Senior Certificate (NSC) examination that learners write (out of 300 marks) plus school-based assessment (out of 100 marks). The curriculum policy document stipulates SEVEN formal tasks that comprise school-based assessment in History.

4. PROGRAMME OF ASSESSMENT AND WEIGHTING OF TASKS

| Term 1 | Term 2 | Term 3 | Term 4 |

| 3 tasks | 2 tasks | 2 tasks | |

|

|

|

|

| 25% of total year mark = 100 marks | 75% of total year mark = 300 marks | ||

5. QUALITY-ASSURANCE PROCESS FOLLOWED

To ensure that there is compliance with the requirements of SBA in History, an example of how to undertake research is given below.

Introduction

The research assignment in Grade 12 accounts for 20% of the total school-based assessment (SBA). It is, therefore, essential that this be a significant piece of work. This assignment offers learners the opportunity to demonstrate their skills, knowledge and understanding of History which they have acquired during the course of the FET phase.

The research assignment can be written on any section of the Grade 12 curriculum. There are, however, two sections in the curriculum, which are not formally examined in the final Grade 12 examination:

- An overview of civil society protests

- Remembering the past: Memorials

It is recommended that one of these topics be investigated as a research project.

Some points to consider when planning a research assignment:

- The choice of research topic needs to be made, taking into consideration the context of your school and the available resources to which learners have access.

- This assignment provides learners with an opportunity to embark on a process of historical enquiry. Conducting original research involves the collection, analysis, organization and evaluation of information, and the construction of knowledge.

- Clear, written instructions with due dates and the assessment criteria must be given to learners at the beginning of the school year to allow adequate time for the preparation and completion of the assignment.

- The progress of learners, with regard to the research assignment, must be monitored on an on-going basis.

- It is essential that learners submit original work. To reduce the likelihood of plagiarism, the key question or research topic should be changed every year.

Learners are expected to fulfil the following requirements in their research assignment:

- Analyse and answer the key question.

- Identify a variety of relevant source materials to help answer the key question.

- Select relevant examples from the source material which can be used to substantiate the line of argument.

- Organise relevant information in order to write a coherent and logical answer to the key question.

- Write an original piece of work, using your own words.

- Correctly contextualise all sources, including Illustrations and maps, which have been included.

- Reflect upon the process of research and consider what has been learnt.

- Include a bibliography of all the resources which have been consulted in the course of researching and writing the assignment.

Some suggestions of what can be done with the research assignments when they are completed:

- The research assignments should be displayed at your school, community hall or local library. Exhibiting the learners’ work is very important. It gives learners a sense of purpose and shows them that their ideas and efforts are of value to their school and community.

- Learners could give an oral presentation of their research projects to the class, grade, school or local community. This gives learners the opportunity to speak about their research and share their ‘new-found’ knowledge.

- Organise a class debate on the key question.

- Hold a History evening at which learners could be given an opportunity to present their work to friends, family and members of the community. Further, this will be an ideal platform to showcase the work of the school’s History department in an endeavour to promote the subject History at the FET level.

TABLE SHOWING HOW TO STRUCTURE AND CARRY OUT RESEARCH

KEY QUESTION: How was the role of women in the struggle against apartheid different from that of men?

| STRUCTURE OF A RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT | SUGGESTIOND ON HOW TO CARRY OUT YOUR RESEARCH |

| Hint 1 Before you start your research |

|

| Cover Page |

|

| Introduction (Write approximately ½ - 1 page) |

|

| Background (Write approximately 1 - 2 page) |

|

| Hint 2 : During the research process |

|

| Body of Essay (Write approximately 2-3 pages) |

|

| Conclusion (Write approximately ½–page) |

|

| Reflection (Write approximately ½–1 page) |

|

| Bibliography |

|

| Hint 3: Before you submit your research assignment |

|

SUGGESTED RUBRIC TO ASSESS A RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT

TOTAL MARKS: 100

| CRITERIA | LEVEL DESCRIPTORS | |||

| LEVEL 4 | LEVEL 3 | LEVEL 2 | LEVEL 1 | |

| Criterion 1 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Planning (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of planning (clear research schedule provided). | Shows adequate understanding of planning. | Shows some evidence of planning. | Shows little or no evidence of planning. |

| Criterion 2 | 16 – 20 | 10 - 15 | 5 – 9 | 0 – 4 |

| Identify and access a variety of sources of information (20 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows adequate understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows some understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows little or no understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. |

| Criterion 3 | 8 – 10 | 5 – 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Knowledge and understanding of the period (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent knowledge and understanding of the period | Shows adequate knowledge and understanding of the period. | Shows some knowledge and understanding of the period. | Shows little or no knowledge and understanding of the period. |

| Criterion 4 | 24 – 30 | 14 – 23 | 7 – 13 | 0 – 6 |

| Historical enquiry, interpretation & communication (Essay) (30 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows adequate understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows some understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows little or no understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. |

| Criterion 5 | 8 – 10 | 5 – 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Presentation (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows adequate evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows some evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows little or no evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). |

| Criterion 6 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Evaluation & reflection (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). | Shows adequate understanding of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from under taking research). | Shows some evidence of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). | Shows little or no evidence of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). |

| Criterion 7 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Acknowledgement of sources (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows adequate understanding of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows some evidence of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows little or no evidence of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). |

ANNEXURE A: EXAMPLE OF A COVER PAGE FOR A RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT:

| GRADE 12 RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT: HISTORY | |

| NAME OF SCHOOL | |

| NAME OF LEARNER | |

| SUBJECT | |

| RESEARCH TOPIC | |

| KEY QUESTION | |

STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY:

I hereby declare that ALL pieces of writing contained in this research assignment, are my own original work and that if I made use of any source, I have duly acknowledged it.

LEARNER’S SIGNATURE:____________________________________________

DATE:_____________________________________________________________

ANNEXURE B: AN EXAMPLE OF A MONITORING LOG

| DATE | ACTIVITY | COMMENT |

| January | Commencement | Learners are given the instructions, guidelines and key question for the research assignment. |

| March | 1st DRAFT:

| |

| April | 2nd DRAFT:

| |

| May |

| |

| July |

|

Teacher’s name:_______________________

Teacher’s signature:___________________

Learner’s signature:____________________

SCHOOL STAMP

|

ANNEXURE C: LIST OF SUGGESTED RESOURCES WITH A SYNOPSIS (IN ITALICS)

BOOKS:

Berger, I., Threads of solidarity: Women in South African industry, (Indiana University Press, 1991).

This book details women’s changing place in formal and casual work. It explores the relationship between women across the colour lines as workers and members of trade unions.

Bernstein, H., For their triumphs and for their tears. Women in Apartheid South Africa. (IDAF, 1985).

This booklet gives a great deal of very useful information about how women lived, worked, struggled and survived in apartheid South Africa.

Bozzoli, B. with Nkotsoe, M., Women of Phokeng (Ravan Press, 1991).

This book traces the life histories and experiences of 22 black women from the small town of Phokeng.

Cock, J., Colonels and cadres. War and gender in South Africa, (OUP, 1991).

This book contains interviews with women who served in both the SADF and MK and analyses their experiences.

Cock, J., Maids and madams. A study in the politics of exploitation, (Ravan Press, 1989).

An investigation into experiences of women domestic workers during apartheid.

Du Preez Bezdrob, A.M. Winnie Mandela a life. (Paarl: Paarl Printers. 2003).

Gordon, S., A talent for tomorrow. Life stories of South African servants (Ravan Press, 1985).

A book that contains the life stories of 23 people, most of whom are women, who worked as domestic labourers under apartheid.

Human, M.; Mutloatse, M. & Masiza, J. The Women’s Freedom March of 1956. (Pan McMillan (Pty Ltd), 2006).

Luthuli, A., Let my people go, The Autobiography of Albert Luthuli. (Paarl Printers, 2006).

Mashinini, E., Strikes have followed me all my life (The Women’s Press, 1989).

The autobiography of Emma Mashinini who was secretary of one of South Africa’s biggest black Trade Unions, the CCAWUSA (the Shop and Distributive Workers’ Union).

Naidoo, P., Footprints in Grey Street. (Ocean Jetty Publishing, 2002).

Platzky, L. & Walker, C., The surplus people. Forced removal in South Africa (Ravan Press, 1985).

The creation of racially separate areas was the cornerstone of apartheid policy. The majority of people who were forcibly removed in order to create this artificial separation were women and children. This book documents their experiences and their struggle to survive.

Vahed, G. & Waetjen,T., Gender modernity and Indian delights. The Women’s Cultural Group of Durban 1954- 2010 (HSRC, 2010).

Part social history part biography, this book shows how the women in the Durban Cultural Group creating an identity for themselves in the context of apartheid.

Walker, C., Women and gender in Southern Africa to 1945. (New Africa Books, 1990). Gives valuable background information about the experience of women in South Africa. It sets the scene for a discussion of the 1950s–1970s.

Walker, C., Women and resistance in South Africa. (Onyx Press, 1991).

This remains the most detailed historical account of women’s resistance during apartheid. Walker has chapters on the Federation of South African Women, Anti-Pass protests, the Women’s Charter of 1954, among others.

South African History Online, ‘For freedom and equality’, Celebrating women in South African history (DBE, no date).

This booklet contains information about women’s involvement in the liberation struggle. There are a number of biographical profiles of great South African women. It can be downloaded from the South African History Online website at: http://www.sahistory.org.za/aids-resources/freedom-and-equality-celebrating-women-south-african history-booklet

Malibongwe Igama Lamakhosikama. Praise be to women. Remembering the role of women in South Africa through dialogue (Nelson Mandela Foundation, 2007).

The text in this booklet is the edited version of the Malibingwe Dialogue which took place on 30 May 2007 at the Nelson Mandela Foundation.

It can be downloaded from the following website: http://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/Malibongwe_WEB.pdf

WEBSITES:

www.blacksash.org.za

Full digital texts of the Black Sash publication Sash is available from 1960-1990.

http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/womens-struggle-1900-1994

South African History Online. This site has a wide range of information about women’s struggles in South Africa 1900-1994.

http://www.anc.org.za/themes.php?t=Women`s%20Struggles

This site, maintained by the ANC, has documents concerning women in the liberation struggle

ORAL INTERVIEWS

There is a saying in Mozambique that ‘our old people are our libraries’. If you are living in an area where it is difficult to access the Internet, or do not have a local library, then remember that the people living in your community have a wealth of information in their memories. You may consider conducting interviews with women and men in your community and recording their stories as evidence to answer your key question.

ANNEXURE D: EXAMPLE OF A TEMPLATE FOR NOTE-TAKING DURING RESEARCH

FULL REFERENCE OF RESOURCE | EVIDENCE (This could be used to support your argument) |

E.g.: | ‘During the 1980s hundreds of thousands of black women were forced to move and were dumped in remote rural areas called Bantustans or ‘homelands’: These forced removals mainly affected women’ (p 23). This extract could be used as evidence that women’s role in the struggle against apartheid was different to men’s role. |

ANNEXURE E: GUIDELINES ON HOW TO WRITE A BIBLIOGRAPHY

- For a book:

Author (last name, initials). Title of book (Publishers, Date of publication).

Example:

Dahl, R. The BFG. (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1982). - For an encyclopaedia:

Encyclopaedia Title, Edition Date. Volume Number, ‘Article Title’, page numbers.

Example:

Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1997. Volume 7, ‘Gorillas’, pp. 50-51. - For a magazine:

Author (last name first), ‘Article Title’. Name of magazine. Volume number, (Date): page numbers.

Example:

Jordan, Jennifer, ‘Filming at the top of the World’. Museum of Science Magazine. Volume 47, No 1, (Winter 1998): p 11. - For a newspaper:

Author (last name first), ‘Article Title’. Name of Newspaper. City, state publication. (Date): edition if available, section, page number(s).

Example:

Powers, Ann, ‘New Tune for the Material Girl’. The New York Times. New York, NY. (3/1/98): Atlantic Region, Section 2, p 34. - For a person:

Full name (last name first). Occupation, date of interview.

Example:

Smeckleburg, Sweets. Bus Driver. 1 April 1996. - For a film:

Title, Director, Distributor, Year.

Example:

Braveheart, Director Mel Gibson, Icon Productions, 1995.

6. ASSESMENT TASKSSOURCE- BASED QUESTIONS

QUESTION 1

WHY DID SOUTH AFRICA BECOME INVOLVED IN THE ANGOLAN CIVIL WAR IN THE 1980s?

SOURCE 1A

The following extract was written by Joseph Hanlon, a journalist, in the mid-1980s. It describes why South Africa became involved in the Angolan civil war and eventually decided to retreat. [From: Beggar Your Neighbours: Apartheid Power in Southern Africa by J Hanlon] |

SOURCE 1B

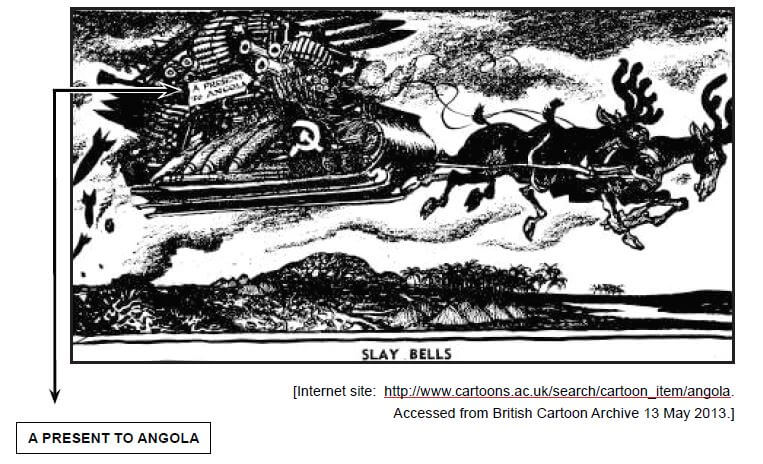

The following is a cartoon by British cartoonist, Leslie Gilbert. It depicts the Soviet Union as Santa Claus on his sleigh, delivering presents in the form of weapons to the MPLA which were used in the civil war against UNITA and the FNLA. The cartoon was entitled ‘Slay Bells’. ‘Slay’ means to kill.

SOURCE 1C

This is part of an interview that was conducted with the former South African Prime Minister, BJ Vorster, by Clarence Rhodes of UPITN-TV (United Press International Television News) on 13 February 1976.

Rhodes: President Kaunda of Zambia described the Soviet and the Cuban intervention in Angola. I think the quote is ‘a plundering (thieving) tiger and its deadly cub’. … Would you say that this then poses a bigger threat than the emergence of yet another independent black African nation on South African borders? [Internet site: http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/interview-south-african-prime-minister-mr-b-j-vorster-mr-clarence rhodes-upitn-tv-13-february. Accessed on 13 May 2013. |

SOURCE 1D

The following is a transcript of a news bulletin that was presented by the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) on 10 August 1982.

Good evening. Another 113 SWAPO terrorists have been killed in continuing Security Force operations aimed at SWAPO bases in southern Angola. The Prime Minister and Minister of Defence have expressed the gov ernment’s sympathy with families of the fifteen South African airmen and soldiers killed. They said events like this shook the people of South Africa, but comfort could be drawn from the fact that the deaths were incurred maintaining civilisation. They sacrificed their lives in the preservation of the norms and values of a Christian community. In the modern world, the barbarian* at the gates is the terrorist**… [From: South Africa: A Different Kind of War by J Frederikse] |

*Barbarian: a negative word used by the apartheid regime to refer to activists from the liberation movements which operated in exile.

** Terrorist: a word used by the apartheid regime to refer to freedom fighters.

QUESTION 2

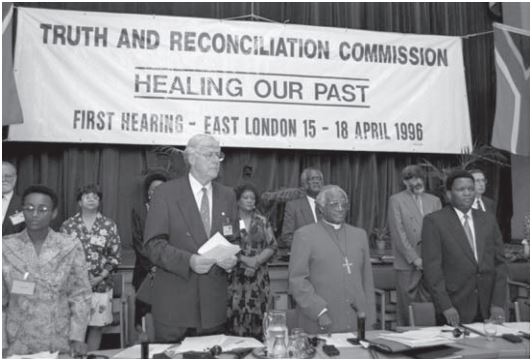

HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) IN HEALING OUR PAST?

SOURCE 2A

This is a photograph of the first Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearing that took place in East London on 15 April 1996.

[Internet site: http://qu301southafrica.com/tag/reconu. Accessed on 3 May 2013]

SOURCE 2B

The following extract focuses on the assassination of anti-apartheid activist and attorney, Griffiths Mxenge, on 20 November 1981.

On 20 November 1981, Mr Griffiths Mxenge was found dead in a cycling stadium at Umlazi. Three Vlakplaas operatives namely, Commander Dirk Coetzee and askaris (spy/sell-out) Almond Nofemela and David Tshikilange were charged and convicted of the killing. Coetzee, Nofemela and Tshikilange applied for amnesty for Mxenge’s killing. [Internet site: www.justice.gov.za/trc/report/. Accessed on 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 2C

The following statement was issued by the Amnesty Committee of the TRC. It focuses on the reasons for the granting of amnesty to Dirk Coetzee, Almond Nofemela and David Tshikilange for the murder of Griffiths Mxenge.

The Amnesty Committee of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission today granted amnesty to Dirk Coetzee, David Tshikalange and Butana Almond Nofomela in respect of the murder of Durban attorney, Mr Griffiths Mxenge, in November 1981. [Internet site: www.info.gov.za/speeches/1997/08050w13297.html. Accessed on 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 2D

The following report by the South African Press Association (SAPA) outlines the reasons for the Mxenge family’s opposition to the process of amnesty.

DURBAN 5 November 1996 — SAPA The family of slain human-rights lawyer, Griffiths Mxenge, on Tuesday said the granting of amnesty to former policeman Dirk Coetzee, who has confessed to ordering Mxenge’s murder, would be a travesty (mockery) of justice ... [Internet site: www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/1996/9611/s961105h.html. Accessed on 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 2E

The following is part of an interview that Shaun de Waal, reporter from the Mail and Guardian, conducted with Mahmood Mamdani about South Africa’s TRC process. Mamdani is an African academic and current director of the Makerere Institute of Social Research.

| Shaun de Waal: So you’re saying the TRC was the performative extension of the settlement reached at Codesa and, for all that, it did help to produce a political solution ... Mamdani: … Yet the TRC defined victims as though no apartheid had ever existed – simply as individuals whose bodily integrity had been violated. That is to put apartheid on the same plane as any dictatorship anywhere in the world. But apartheid affected the entire society, not just isolated individuals. Its cutting edge was legislation that defined the whole population into groups it called races, then it passed laws that enabled a minority and disabled the majority ... [From: Mail and Guardian, 3–9 May 2013 |

QUESTION 3

WHAT IMPACT DID GLOBALISATION HAVE ON THE NEW WORLD ORDER?

SOURCE 3A

The following extract focuses on the phenomenon of globalisation.

Globalisation is the system of interaction among the countries of the world in order to develop the global economy. Globalisation refers to the integration of economics and societies all over the world. Globalisation involves technological, economic, political, and cultural exchanges made possible largely by advances in communication, transportation and infrastructure. [Internet site: http://hubpages.com/hub/Definition-of-Globalization. Accessed 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 3B

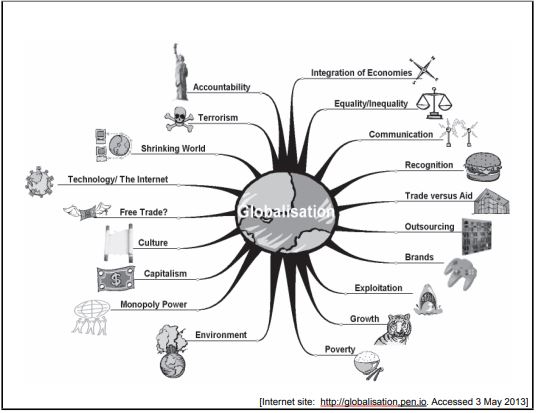

The following source is a diagrammatic representation of the different features of globalisation.

[Internet site: http://globalisation.pen.io. Accessed 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 3C

The following article by the World Economic Forum Survey focuses on how people from 25 countries viewed globalisation.

People around the world increasingly favour globalisation but worry about jobs, poverty and environment The largest-ever public opinion poll on globalisation, covering countries with 67 per cent of the world’s population, shows that people increasingly favour economic globalisation, but they have high expectations in some areas that will be difficult to satisfy. Citizens also have concerns about what they see as the damaging impacts of globalisation.

The World Economic Forum poll involved 25 000 in-person or telephone interviews across mainly ‘Group of 20’ countries and was conducted between October and December 2001 ... Majorities of people in 19 of 25 countries surveyed expect that more economic globalisation will be positive for themselves and their families. While over six in ten citizens worldwide (62 per cent) see globalisation as positive ... The strongest supporters are found in northern Europe, North America, and poorer countries in Asia ... [Internet site: www.globescan.com/news_archives/press_inside.htm. Accessed 3 May 2013] |

SOURCE 3D

The following article by Prabhakar Pillai is entitled ‘The Negative Effects of Globalisation’. It focuses on his views about globalisation.

In order to cut down costs, many firms in developed nations have outsourced their manufacturing and white-collar jobs to ‘Third-World’ countries like India and China, where the cost of labour is low. The most prominent among these have been jobs in the customer-service field as many developing nations have a large English-speaking population – ready to work at one-fifth of what someone in the developed world may call ‘low-pay’ ... [Internet site: http://www.buzzle.com/articles/negative-effects-of-globalization.html. Accessed 03 May 2013] |

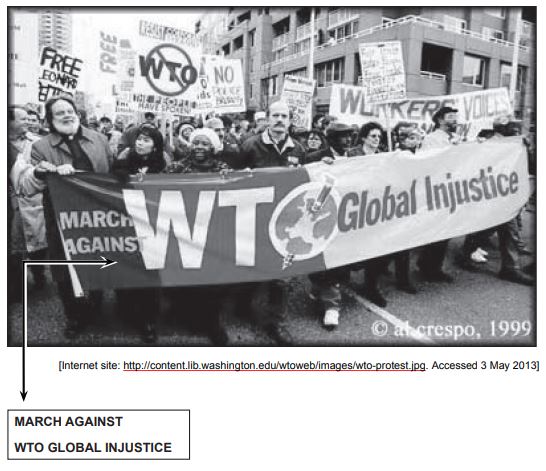

SOURCE 3E

A photograph showing activists protesting against the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in Washington in 1999.

MARCH AGAINST WTO GLOBAL INJUSTICE

|

QUESTION 1

WHY DID SOUTH AFRICA BECOME INVOLVED IN THE ANGOLAN CIVIL WAR?

Study Sources 1A, 1B, 1C and 1D to answer the questions that follow.

1.1 Refer to Source 1A.

1.1.1 Which organisation did the apartheid government support during the Angolan civil war? (1 x 1) (1)

1.1.2 List FOUR Angolan economic installations that were targeted by the South African Defence Force. (4 x 1) (4)

1.1.3 Using the information in the source, explain THREE reasons why the apartheid government felt threatened by the MPLA leadership in Angola. (3 x 2) (6)

1.1.4 In the context of the Angolan civil war, explain why the MPLA requested assistance from Cuba and the USSR. (1 x 3) (3)

1.2 Study Source 1B.

1.2.1 What message does the cartoon convey regarding the Soviet Union’s support for the MPLA in Angola? Explain your answer using the visual clues in the cartoon. (2 x 2) (4)

1.2.2 Explain to what extent this cartoon may be regarded as biased. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3 Consult Source 1C.

1.3.1 According to Kaunda, which TWO communist countries supported the MPLA? (2 x 1) (2)

1.3.2 Define the term communism in your own words. (1 x 2) (2)

1.3.3 Explain why Prime Minister Vorster did not consider Angola as ‘an independent black African country’. (2 x 2) (4)

1.3.4 Comment on Prime Minister Vorster’s reference to the word ‘communists’ in the context of the Angolan civil war. (1 x 2) (2)

1.4 Use Source 1D.

1.4.1 Quote TWO negative words that were used to describe the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) on the SABC news bulletin. (2 x 1) (2)

1.4.2 How did the SABC justify the deaths of the 15 SADF airmen and soldiers who were killed in Angola? (2 x 2) (4)

1.4.3 Explain to what extent the information in Source 1D would be useful for a historian researching the use of propaganda during South Africa’s participation in the Angolan civil war. Use relevant examples from the source to support your answer. (2 x 2) (4)

1.5 Use the information in the relevant sources and your own knowledge, to write a paragraph of about 8 lines (about 80 words) explaining why South Africa became involved in the Angolan civil war. (8)

[50]

QUESTION 2

HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) IN HEALING OUR PAST?

Study Sources 2A, 2B, 2C and 2D to answer the questions that follow.

2.1 Study Source 2A.

2.1.1 When and where was South Africa’s first TRC hearing held? (2 x 1) (2)

2.1.2 Define the concept reconciliation in your own words. (1 x 2) (2)

2.1.3 Explain why the TRC chose to use the slogan ‘Healing Our Past’ during its hearings, as shown in the photograph. (1 x 2) (2)

2.1.4 Comment on why you think the TRC was considered to be a significant event in South Africa’s history. (1 x 3) (3)

2.2 Consult Source 2B.

2.2.1 Name the THREE apartheid operatives who were charged with the murder of Griffiths Mxenge. (3 x 1) (3)

2.2.2 How, according to Nofemela, was Griffiths Mxenge murdered? (2 x 2) (4)

2.2.3 Why, do you think, were the three apartheid operatives found guilty of the killing of Mxenge but not sentenced? Support your answer with relevant evidence. (2 x 2) (4)

2.3 Use Source 2C.

2.3.1 Explain why the THREE apartheid operatives were granted amnesty. (1 x 2) (2)

2.3.2 ‘It will not be necessary for the trial court to proceed with the question of sentence.’ Why, do you think, was this statement made? (1 x 2) (2)

2.4 Refer to Sources 2B and 2C. Explain to what extent an historian would consider the information in Sources 2B and 2C useful when writing about the granting of amnesty to those responsible for the death of Griffith’s Mxenge. (2 x 2) (4)

2.5 Read Source 2D.

2.5.1 How did Griffiths Mxenge’s family react to the application for amnesty of the three apartheid operatives? (1 x 2) (2)

2.5.2 Explain why the Mxenge family responded in this manner to the granting of amnesty to the three apartheid operatives. (2 x 2) (4)

2.6 Consult Source 2E.

2.6.1 How does Mamdani view the manner in which the TRC dealt with the victims of apartheid? (1 x 2) (2)

2.6.2 Mamdani suggests that the TRC process was flawed. What change did he propose that might have made the TRC more successful in its attempt to ‘heal’ the past? (1 x 2) (2)

2.6.3 Comment on the meaning of Mamdani’s statement: ‘The TRC was only interested in, ‘Did you give the orders in this case, that case?’ ‘ (2 x 2) (4)

2.7 Use the information in the relevant sources and your own knowledge, to write a paragraph of about 8 lines (about 80 words), explaining to what extent the TRC was successful in healing our past. (8)

[50]

QUESTION 3

WHAT IMPACT DID GLOBALISATION HAVE ON THE NEW WORLD ORDER?

Study sources 3A, 3B, 3C, 3D and 3E and answer the questions that follow.

3.1 Use Source 3A.

3.1.1 Define the term globalisation in your own words. (1 x 2) (2)

3.1.2 Quote the TWO types of integration mentioned in the source in the context of globalisation. (2 x 1) (2)

3.1.3 According to the information in the source, what might be the negative effects of removing tariffs on the economies of developing countries situated on the African continent? (2 x 2) (4)

3.2 Study Source 3B.

3.2.1 Using the information in the source, identify THREE features of globalisation. (3 x 1) (3)

3.2.2 Explain whether you think these changes (as identified in QUESTION 3.2.1) have had a positive or a negative impact on the various countries of the world. Support your answer with relevant evidence. (3 x 2) (6)

3.3 Refer to Source 3C.

3.3.1 According to the information in the source, why did an increasing number of people favour economic globalisation? (1 x 2) (2)

3.3.2 Quote any TWO positive aspects that the global survey revealed about globalisation. (2 x 1) (2)

3.3.3 As a historian, explain the limitations of using this source when researching the effects of globalisation. (1 x 3) (3)

3.4 Consult Source 3D.

3.4.1 Identify FOUR negative effects of globalisation. (4 x 1) (4)

3.4.2 Explain how globalisation contributed to the negative effects (as identified in QUESTION 3.4.1). Support your answer with a valid reason. (1 x 2) (2)

3.5 Refer to Sources 3C and 3D. Explain how the information in these sources would be useful to a historian studying globalisation. (2 x 2) (4)

3.6 Refer to Source 3E.

3.6.1 What TWO factors, do you think, prompted activists to embark on protest action? (2 x 1) (2)

3.6.2 Comment on the significance of the words, ‘Global Injustice’, as shown on the banner, in the context of globalisation. (1 x 2) (2)

3.7 Consult Source 3D and Source 3E and explain how the information in these sources support each other regarding the negative effects of globalisation. (2 x 2) (4)

3.8 Use the information from the relevant sources and your own knowledge, to write a paragraph of about 8 lines (about 80 words), explaining how globalisation has created a new world order from 1989 to the present. (8)

[50]

6. ASSESSMENT TASKS: ESSAY QUESTIONS

1. TOPIC 1: CHINA OR VIETNAM

QUESTION 1A: CHINA

Discuss to what extent Mao transformed China from an underdeveloped country to a super power between 1949 and 1976. [50]

QUESTION 1B: VIETNAM

‘ ... All the military might of a superpower could not defeat a small nation of peasants.’

Critically discuss this statement in the light of United States of America’s involvement in Vietnam between 1965 and 1975. Use relevant examples to support your answer. [50]

2. TOPIC 2: INDEPENDENT AFRICA

QUESTION 2: CONGO AND TANZANIA

Write a comparative essay on the political successes and challenges that post-colonial leaders of both the Congo and Tanzania faced between the 1960s and the 1980s. [50]

3. TOPIC 4: CIVIL RESISTANCE IN SOUTH AFRICA: 1970S TO 1980S

QUESTION: 4: THE CRISIS OF APARTHEID IN THE 1980S

Explain how internal mass civic resistance and international pressure contributed to the demise (fall) of the apartheid regime in the 1980s. [50]

4. TOPIC 5: THE COMING OF DEMOCRACY IN SOUTH AFRICA AND THE COMING TO TERMS WITH THE PAST

QUESTION: 5: THE NEGOTIATED SETTLEMENT AND THE GOVERNMENT OF NATIONAL UNITY

Allister Sparks argues that the process of negotiation ‘was always a crisis-driven process’.

Critically assess Allister Spark’s statement with reference to the process of negotiation in South Africa between 1990 and 1994. [50]

7. GUIDELINES FOR LEARNERS AND TEACHERS:

EXEMPLAR RESPONSES:

RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT

GRADE 12: RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT

| SCHOOL: | XYZ SECONDARY SCHOOL |

| NAME OF LEARNER: | LA DUMA |

| SUBJECT: | HISTORY |

QUESTION: ‘The women of South Africa have been leading the struggle hand in hand with the men. There has never been any difference except that the women’s side is more vulnerable to any oppression, the side of their home and the children.’ (Albertina Sisulu) |

STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY

I HEREBY DECLARE THAT ALL PIECES OF WRITING CONTAINED IN THIS RESEARCH ASSIGNMENT, ARE MY OWN ORIGINAL WORK AND THAT IF I MADE USE OF ANY SOURCE, I HAVE DULY ACKNOWLEDGED IT.

LEARNER’S SIGNATURE:________________________________________

DATE:______________________

A POEM PAYING TRIBUTE TO SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN

Praise to our Mothers

If the moon were to shine tonight

To light up my face and show off my proud form

And a soft easy flowing dress with the colours of Africa

If I were to stand on top of a hill

And raise my voice in praise

Of the women of my country

Who have worked throughout their lives

Not for themselves, but for the very life of all Africans

Who would I sing my praises to?

I could quote all the names

Yes, but where do I begin?!

Do I begin with the ones

Who gave their lives

So that we others may live a better life

The Lilian Ngoyis, the Victoria Mxenges

The Ruth Firsts

Or the ones who have lost their men

To Robben Island and their children to exile

But carried on fighting

The MaMotsoaledis, the MaSisulus

The Winnie Mandelas?

Or maybe I would sing praises to

The ones who have had the resilience

And cunning of a desert cobra

Priscilla Jana, Fatima Meer, Beauty Mkhize

Or the ones who turned deserts into green vegetable gardens

From which our people can eat, Mamphela Ramphele, Ellen Khuzwayo

Or would the names of the women

Who marched, suffered solitary confinement

and house arrests

Helen Joseph, Amina Cachalia, Sonya Bunting, Dorothy Nyembe,

Thoko Mngoma, Florence Matomela, Bertha Mkhize,

How many more names come to mind

As I remember the Defiance Campaign

The fights against Beer Halls that suck the strength of our men

Building of alternative schools away from Bantu Education

And the fight against pass laws

Maybe, maybe, I would choose a name

Just one special name that spells out light

That of Mama Nokukhanya Luthuli

Maybe if I were to call out her name

From the top of the hill

While the moon is shining bright;

No — Ku — Kha — nya!

NO — KU — KHA — NYA!!!

To reach all the other women

Whose names are not often mentioned

The ones who sell oranges and potatoes

So their children can eat and learn

The ones who scrub floors and polish executive desktops in towering office blocks While the city sleeps

The ones who work in overcrowded hospitals

Saving lives, cleaning bullet wounds and delivering new babies

And the ones who have given up

Their places of comfort and the protection of their skin colour Marian Sparg,

Sheena Duncan,

Barbara Hogan, Jenny Schreiner.

And what of the women who are stranded in the homelands

With a baby in the belly and a baby on the back

While their men are sweating in the bowels of the earth?

May the lives of all these women

Be celebrated and made to shine

When I cry out Mama Nokukhanya’s name

NO — KU — KHA — NYA!!!

And we who are young, salute our mothers

Who have given us

The heritage of their Queendom!!!

Gcina Mhlophe

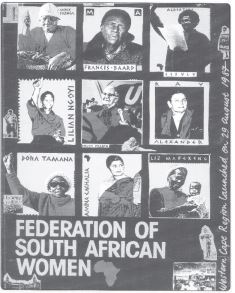

A FEDSAW poster commemorating the role of South African women in the struggle for freedom. Taken from Celebrating Women in South African History.

MONITORING LOG OF LA DUMA – GRADE 12C

| DATE | ACTIVITY | COMMENT |

| JANUARY 2014 | Commenced | Key question finalised |

| FEBRUARY | FIRST DRAFT

| References in bibliography include a variety of sources: books, magazine articles, interviews, etc. |

| APRIL | SECOND DRAFT

| Draft was submitted. Comments made by teacher and returned to learner for re-working. |

| MAY | SUBMIT FINAL COPY | |

| JULY | FEEDBACK | Project was moderated at three levels: School, cluster and district. |

| AUGUST | Presentation of projects to school and community. |

TEACHER’S NAME: Mrs BA Starr

TEACHER’S SIGNATURE:___________________________________

LEARNER’S SIGNATURE:_____________________________________

SCHOOL STAMP:

|

INTRODUCTION

This research project examines the role played by women during the liberation struggle and attempts to answer the question of how different the role of women was to that of men during the struggle against apartheid. Albertina Sisulu, one of the most important leaders of the anti-apartheid resistance, has argued that women fought ‘side-by side’ with men; but she also suggested that they were particularly vulnerable to oppression because of their role as mothers and wives. This research assignment presents evidence which supports Albertina Sisulu’s statement. In answering this question, I have studied a variety of sources. These sources include books by historians, documents, oral sources, the Internet and other media. My approach is to look at the strategies employed by a selection of dedicated women who played a key role in the liberation struggle.

In The Women’s Federation March of 1956, Lilian Ngoyi, is singled out as one of the significant leaders who represented the struggle of millions of black South African women.

‘She found herself, as do millions of black women across the land, the victim of both race and sex discrimination. She demonstrated that it was possible not only to transcend the limits imposed on her in this way, but that the struggle in South Africa could not be successfully waged unless women and women’s issues constituted a central part of liberation strategy. Neither the state with all its might, nor morality could really silence these phenomenal women’

(Human, M., Mutloatse, M. & Masiza, J. 2006:62).

This statement is the starting point of my research assignment. It has been said that during apartheid millions of black South African women faced the triple oppression of being black, being women and being poor. This research assignment shows how some women challenged the social convention that women should look after the home, and men should be the authority figure and play a central role in politics. The women discussed in this assignment demonstrated that during the apartheid years, women not only played a key role as wives and mothers but also as political activists and anti-apartheid campaigners. In addition, although there was no feminist movement in South Africa in the apartheid period, sometimes black and white women did unite to fight against apartheid, for example, the anti-pass protest in 1956 organised by the non-racial Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW).

I seek to identify how South African women fought to overcome the many challenges and limitations imposed on them because of their gender as well as by the repressive policies of the National Party government.

BACKGROUND

The resistance by black women to racial inequality in South Africa began long before apartheid was officially introduced in 1948. As early as 1912, women were involved in a passive resistance campaign in support of the black and Indian miners who were striking for better wages and improved working conditions. Also, in 1913, in the Free State, black and Coloured women resisted the carrying of passes.

In 1918, Charlotte Maxeke established the Bantu Women’s League to resist the pass laws. The reason they joined the Bantu Women’s League and not the ANC was due to the fact that women were not allowed to be members of the ANC at that time. The resistance of women to the racially discriminating laws continued into the 1930s. The activism of women took on a new dimension when women were finally permitted to join the ANC in 1943. In addition, they formed the ANC’s Women’s League and Ida Mtwana became the first president.

In 1948, the National Party government came to power and introduced the policy of apartheid in South Africa. During the apartheid years (1948–1994), South Africa was a divided society where people’s status and rights were determined by their race. It was a country where the minority white government passed laws to segregate and discriminate against the majority black population. This policy included laws such as the Population Registration Act that classified all South Africans according to race and the Group Areas Act that forced people to live in racially segregated areas. There were many women who reacted with anger, frustration and outrage at these unfair and unjust laws. Many of these women became anti-apartheid activists and their resistance to apartheid cost them dearly.

During the 1950s, women became more militant and in 1952, the Defiance Campaign drew many women into civil disobedience and activism against the unjust apartheid laws. Partly in response to their experiences during the Defiance Campaign, a new women’s organisation was established in 1954. The Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW) united women of all racial groups, from various organisations, including the ANC, the SAIC (South African Indian Congress), the Non-European United Front, various trade unions and civic associations. This was a multi-racial women’s organisation which included teachers, nurses and factory workers as well as housewives. These women pledged to draw up a Women’s Charter to end inequality. This Women’s Freedom Charter began with the words:

‘We, the women of South Africa, wives and mothers, working women and housewives, African, Indian, European and Coloured, hereby declare our aims of striving for the removal of all laws, regulations, conventions and customs that discriminate against us as women and that deprive us in any way of our inherent right to the advantages, responsibilities and opportunities that society offers to any one section of the population.’

In 1956 FEDSAW jointly organised a 20 000 strong march to the Union Buildings in Pretoria to protest against the extension of the pass laws to African women. Although this campaign did not lead to a repeal of the pass laws, the show of strength and unity by women encouraged other women to continue the struggle. In the decades that followed women continued to persevere and pursue the dream of equality and a democratic South Africa.

BODY OF ESSAY

The men and women involved in the liberation struggle paid a heavy price for democracy and freedom:

‘These were people who sacrificed families, homes, communities and incomes. They weren’t home for bedtimes and quality time. They weren’t there to talk after a bad day. They missed their parents’ funerals and cousins’ weddings. Freedom was won by those that dreamt up a maybe, an element of uncertainty, a risk’ (Naidoo, P., 2002:12).

This research assignment focuses on ‘these people’. In particular, it focuses on the women who sacrificed time with their children and families to pursue the struggle against apartheid. I intend to show how these women stepped out of their conventional domestic roles to play an important part in the liberation movement in South Africa. Through their experiences we can better understand that political freedom in South Africa has come at a cost.

Women played many different roles in the struggle. They raised their own children and the children of others, held down jobs and maintained households. They also defended the oppressed, established new organisations, supported the families of political prisoners and those in detention. They helped to establish organisations, hospitals, colleges and institutes, assisted the unemployed, obtained scholarships for the underprivileged, organised protests, attended conferences, travelled abroad, lectured. They were banned, placed under house arrest, detained, imprisoned and in some cases were killed for demanding democracy and equal rights for all South Africans.

Albertina Sisulu, was one such woman. She was a nurse, a mother, a wife and became one of the most important anti-apartheid political activists, earning her the title ‘Mother of the Nation’ for her selfless dedication to the liberation struggle. She took on leadership positions in both the ANC Women’s League and the Federation of South African Women.

Albertina Sisulu became the first woman to be arrested under the General Laws Amendment Act and was jailed for two months, during which she was harassed and taunted psychologically. She was placed in solitary confinement in 1981 and 1985, banned and subjected to house arrest. The book, Winnie Mandela, A Life, recounts Albertina Sisulu’s support of Winnie Mandela in prison:

‘As a result of the appalling conditions and the shock of her situation, she started haemorrhaging. Terrified that she was having a miscarriage, Winnie sank to her knees and buried her head in her hands. Albertina Sisulu, a trained midwife, realised that something was terribly wrong, and pushed the women surrounding Winnie out of the way so that there was enough room for her to lie down. Albertina took off her own jacket and wrapped it around Winnie to keep her warm, and gave strict instructions that she was not to move. The simple, basic care paid off, and Winnie’s baby was saved’

(Du Preez Bezdrob, 2003:78)

This was an unwavering act of compassion. It also shows the vulnerability of women activists during their fight for freedom.

As a ‘negotiator’ in the political arena, Albertina Sisulu established international networks and support bases for the anti-apartheid movement. In the late 1980s she led a delegation of the United Democratic Front (UDF) leaders to Europe to meet British Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, and to the USA to meet US President, George Bush Sr. to gain support for the liberation movement. In 1994, Albertina Sisulu served as a member of parliament in South Africa’s first democratic government. These examples from Sisulu’s life story illustrate the role that women played as activists, but also show that at times women experienced their oppression differently to men.

Another woman who played a key role in the liberation struggle was Fatima Meer. Born in Durban, Meer was the daughter of an ordinary shop assistant, journalist and editor of Indian Views. Durban is a multi-cultural city and Meer established the Durban and District Women’s League to promote good relations between Indians and Africans and through this organisation initiated a number of social-welfare projects.

In 1946 Fatima Meer participated in the passive resistance campaign organised by the South African Indian Congress against apartheid laws. In 1952 she took part in the Defiance Campaign which had been inspired by SAIC’s earlier campaign and four years later in the women’s anti-pass campaign.

Fatima Meer was also a close friend of Nelson and Winnie Mandela and served six months in detention with Winnie Mandela because of her involvement with the Black Women’s Federation. In her book, Higher than Hope, Fatima Meer recalled that Nelson Mandela did not even discuss some of his decisions with his family, but took it for granted that their support would be unconditional. Therefore, women also need to be acknowledged for the supporting role they played and the way they suffered as a result of their husbands’ and fathers’ involvement in resisting the apartheid government.

Like many of her male comrades, Fatima Meer was banned from 1952 to 1954 under the Suppression of Communism Act. Her banning orders restricted her movements and she could not publish or engage in any political activity.

During the 1960s Fatima Meer lectured in the sociology departments at the Universities of Natal and the Witwatersrand (this in itself was a noteworthy achievement for a woman at that time), and took a particular interest in education. In 1953 the Black Education Act was introduced by HF Verwoerd. This Act had a devastating impact on the South African black population as it delivered an unequal, inferior education system. Black children were educated to become unskilled labour and to remain inferior in apartheid society. Meer was aware that there was a high illiteracy rate among Africans, both in townships and rural schools where children had little access to formal education. In order to address the desperate need for education among the African population, she initiated school building programmes in Umlazi, Port Shepstone, Phambili and Inanda. She also established a craft centre in Phoenix and later founded the Khanyisa school project for African children and the Tembelihle Tutorial College to train African students in secretarial skills and established a craft centre for the unemployed to teach them sewing and knitting. Meer’s projects helped to empower black women by teaching them skills that allowed them to become self-sufficient and self-employed in order to better support their families.

It is clear that Meer channelled much of her human resources into trying to improve the quality of education amongst black South African children and saw that this was important to help realise the dream of a South African democracy.

Another great woman activist was Lilian Masediba Ngoyi. She was the daughter of a miner and a domestic worker. She played a significant role in the struggle as a teacher, an activist, a treason trialist, a trade unionist, a founding member of FEDSAW and later became president of the ANC Women’s League. Ezekiel Mphahlele described her as ‘the woman factory worker who is tough granite on the outside, but soft and compassionate deep down in her...’ (Human, M.; Mutloatse & Masiza,J., 2006:63).

Lilian Ngoyi also played a pivotal role during the Defiance Campaign when she was arrested for using a post office reserved for whites only. The prominent presence of women during this campaign, alongside their male counterparts, strengthened the unity that existed in the struggle against repression in South Africa.

As a founding member of the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW), she played a key role in organising the anti-pass demonstration to Pretoria in 1956. The introduction of passes for women was an attack on women’s domestic roles, their ability to look after their children and their homes, which forced many into political activism. In a letter to government, FEDSAW stated the following:

‘At a Congress of Mothers held in Johannesburg in August 1955, the many women present unanimously passed a resolution that a mass deputation of women of all races should be sent to the Union Building … As women, we shall protest particularly against the proposed extension of the pass system to African women and against the housing conditions in which many thousands of African families must live.’

During the women’s march to the Union buildings on 9 August 1956, the women famously told the Prime Minister Strijdom:

‘WATHINT’ ABAFAZI, WATHINT’ IMBOKOTHO

YOU’VE TAMPERED WITH THE WOMEN

YOU’VE KNOCKED AGAINST A ROCK’

HISTORY SCHOOL-BASED ASSESSMENT EXEMPLARS – 47 CAPS GRADE 12 TEACHER GUIDE

Albert Luthuli, former president of the ANC, described the strength of women during the anti-pass march to Pretoria by saying:

‘Our women have played a major part in conferences and demonstrations. Furthermore, women of all races have had far less hesitation than men in making common cause about things basic to them’ (Luthuli, A., 2006:188).

This was an example where women of all races united to resist the repressive apartheid government. This point of view was reinforced by Albertina Sisulu when she said:

‘Well, the 9th of August to us was an eye-opener. In the sense, that we thought that men could really be the people to carry reference books. But when it turned to us, we felt it’s something else now. So, all we had to do was to rally the women against you, you know accepting the reference books for women. Because we said, you know, we have got our reference books, our children to look after we just had no business and did not have any business to carry passes like men. We have seen the problem, what the passes have done to our men – being arrested at work and you are waiting for him. Let us say no to the reference books’

(Human, M.; Mutloatse & Masiza, J., 2006:113).

Lillian Ngoyi was arrested in 1956 for high treason. She spent a significant amount of time in solitary confinement. An extract from her biography highlights the price that she paid for her activism against the apartheid regime:

‘The authorities were determined to silence Lillian and, in 1962 she was given further restrictions, confining her to her suburb of Orlando in Soweto. She survived as best she could, sewing from home. The Special Branch (Security Police) would try to scare away her customers by threatening them with prison, or accusing them of subversive activities …’

(Quoted in Bottaro, J.; Visser, P. & Worden, N., 2012:206).

For Ngoyi’s selfless struggle in fighting against the apartheid regime the ANC awarded her the prestigious Isitwalandwe/Seaparankoe Award.

One of the other leaders in the 1956 women’s march to Pretoria was Helen Joseph. Born in England, Joseph came to South Africa as a teacher in 1931. After leaving to serve in the Air Force in World War II, she returned and worked with the Garment Workers Union as a Social Welfare Officer. Here she met Solly Sachs, who was a communist hated by Afrikaner nationalists for organising young Afrikaans women into a multi-racial Garment Workers’ Union. Joseph also joined the South African Congress of Democrats (SACOD), an organisation that was affiliated to the ANC and encouraged white activism against apartheid.

Before moving to South Africa, Joseph had worked as a teacher in India and came to embrace the meaning behind the Hindu greeting ‘namaste’ (the God in me honours the God in you). If God is in everyone, how could we ever discriminate, or fail to help those who are harmed? This philosophy influenced her to act against the inequalities of apartheid.

Helen Joseph had the opportunity to read out the clauses of the Freedom Charter at the Congress of the People and played a key role in the formation of FEDSAW and the women’s march in 1956. Alongside other anti-apartheid activists, Joseph was arrested and charged with high treason and banned in 1957. While in prison she suffered great hardship and humiliation at the hands of the government officials, which she faced with courage, and single minded determination. The evidence below illustrates the strength and commitment of these women in the struggle for freedom.

From the police cells, the women were moved to the Fort, the prison in Braamfontein which was totally unprepared for the sudden influx of so many awaiting-trial prisoners. There were not enough blankets, sleeping mats, toilets or food for the women, who milled around in the main hall and on a second-floor balcony while waiting to be processed. They were lined up in groups, ordered to undress, and told to squat so that warders could conduct vaginal searches for contraband. Then the women were told to dress again and shown to the cells – filthy, stinking and lice-riddled. (Du Preez Bezdrob, 2003:77)

In the book, Winnie Mandela A Life, we come across the strength shown by Helen Joseph and others who endured difficult circumstances in their fight for liberation. She became a good friend of Winnie Mandela and was regarded as a mother figure. She provided advice and support for others. Therefore, we can appreciate her role as adviser and friend. Helen Joseph, together with the Anglican Church, arranged for those who could not be visited to be sent money by postal order from family members. Her role can be seen as a humanitarian reaching out to those in distress. Helen Joseph was awarded the ANC’s highest award Isitwalandwe/Seaparankoe medal to symbolise integrity and courage.

The youngest leader of the 1956 Woman’s march was Sophie Williams. Born in Port Elizabeth, she went to work in a textile factory as a young girl. She soon became known for her negotiating skills and was appointed as shop steward within the Textile Workers’ Union. She was identified as a leader while still a teenager and in 1955 was appointed as the full-time organiser for the Coloured People’s Congress in Johannesburg. In the 1960s Williams followed her husband, Benny de Bruyn, into exile where she worked for the ANC in Zambia and Tanzania. After years of activism in exile, Williams returned to South Africa in 1990 when opposition parties were unbanned. Her role in the struggle had taken a different path to that of those women who had remained in South Africa but she continued to play a role in the struggle for a democratic South Africa.

CONCLUSION

In answering the key question on how different the role of women was to that of men during the apartheid struggle, I have highlighted the roles played by some of the most significant South African women. In attempting to do this, I looked at the strategies they employed and the different forms of protest undertaken by women as compared to that of men. There were many other women who played an important role in the liberation struggle, for example Ray Alexander, Elizabeth Mafekeng, Frances Baard, Mabel Balfour, Mary Moodley, Liz Abrahams, Viola Hashe, Rita Ndzanga and Phylis Naidoo. Many other women, ordinary mothers, wives and workers who were not known outside their communities, the unsung heroines of the struggle, also played a very important role. Due to space constraints I have been unable to discuss more examples in this research project.

I have identified how various South African women challenged the National Party government and, in the end, succeeded. In his book, Let My People Go, Albert Luthuli portrays African women as ‘a formidable enemy of the oppression’ (Luthuli, A., 2006:187). In my research assignment, it is evident that the strength and determination shown by women, inspired and encouraged their husbands, brothers, sons and comrades who fought alongside them during the struggle for freedom and challenged the National Party government. Luthuli made the prophetic observation:

There will be enormous, peaceful change in South Africa before the end of this century. People of all races will eventually live together in harmony because no one, white, black or brown wants to destroy this beautiful land of ours. Women must play an increasingly important role in all areas of the life of the future. They were and remain the most loyal supporters in all our struggles. (Luthuli, A, 2006: p.xxii)

This quotation is from of one of our four South African Nobel Prize winners and acknowledges the significant role played by women in all spheres of life. During the apartheid years women undertook various multi-tasking roles – as wives, mothers, workers and activists. Their roles played in the liberation struggle must never be forgotten. South Africa salutes all women.

EVALUATION AND REFLECTION

I have learnt a lot from writing this assignment. I did not know that women had played such a large role in the struggle or that they had suffered so much. Writing this research project was very difficult and I had to organise my time very well. I used the local library and it took a long time to read and organise my notes. My teacher made useful comments on both my first and second drafts of this project which gave me direction and focus. I reorganised material and tried harder to use the life stories of the women I had chosen to study to answer the key question. I think I should have said more about these women’s family lives as well but it was quite difficult to find information and I ran out of space and time. I enjoyed researching and writing this assignment, although it took up a great deal of time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Angier, K. (et al), Viva History Grade 12: Learner’s Book. (Johannesburg: Vivlia, 2013).

Bottaro, J.; Visser, P. & Worden, N., In Search of History. Grade 11. Learner’s Book. (Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman (Pty) Ltd, 2012).

Du Preez Bezdrob, A.M., Winnie Mandela a life. (Paarl: Paarl Printers, 2003).

Friedman, M.; Saunders, C.; Jacobs, M.; Seleti, Y.; & Gordon, J., Looking into the Past. Grade 11 Learner’s Book. (Cape Town: CTP Printers, 2011).

Human, M.; Mutloatse, M.; Masiza, J., The Women’s Freedom March of 1956. (Johannesburg: Pan McMillan (Pty Ltd), 2006).

Light, J. & Johanneson, B., Celebrating Women in South African History (www.sahistory.org.za,) (DBE, 2012).

Luthuli, A., Let My People Go, The Autobiography of Albert Luthuli. (Paarl: Paarl Printers, 2006).

Naidoo, P., Footprints in Grey Street. (Durban: Ocean Jetty Publishing, 2002).

Pillay, G. (et al), New Generation History Grade 12: Learner’s Book. (Durban: Interpak Printers, 2013).

Shaw, G., Believe in miracles, South Africa from Malan to Mandela - and the Mbeki era. (Paarl: Paarl Printers, 2007).

Retrieved from: http://heritage. The times.co.za/memorials/gp/Lilian Ngoyi/article on 4 June 2013.

Retrieved from: http:// www.sahistory.org.za/people/professor Fatima Meer on 4 June 2013.

Retrieved from: http:// www.sahistory.org.za/people/lillian-masediba-ngoyi on 4 June 2013.

ASSESSMENT RUBRIC

| CRITERIA | LEVEL DESCRIPTORS | |||

| LEVEL 4 | LEVEL 3 | LEVEL 2 | LEVEL 1 | |

| Criterion 1 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Planning (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of planning (clear research schedule provided). | Shows adequate understanding of planning. | Shows some evidence of planning. | Shows little or no evidence of planning. |

| Criterion 2 | 16 – 20 | 10 - 15 | 5 – 9 | 0 – 4 |

| Identify and access a variety of sources of information (20 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows adequate understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows some understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. | Shows little or no understanding of identifying and accessing sources of information. |

| Criterion 3 | 8 – 10 | 5 – 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Knowledge and understanding of the period (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent knowledge and understanding of the period | Shows adequate knowledge and understanding of the period. | Shows some knowledge and understanding of the period. | Shows little or no knowledge and understanding of the period. |

| Criterion 4 | 24 – 30 | 14 – 23 | 7 – 13 | 0 – 6 |

| Historical enquiry, interpretation & communication (Essay) (30 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows adequate understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows some understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. | Shows little or no understanding of how to write a coherent argument from the evidence collected. |

| Criterion 5 | 8 – 10 | 5 – 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Presentation (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows adequate evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows some evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). | Shows little or no evidence of how to present researched information in a structured manner (e.g. cover page, table of contents, research topic). |

| Criterion 6 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Evaluation & reflection (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). | Shows adequate understanding of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from under taking research). | Shows some evidence of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). | Shows little or no evidence of evaluating and reflecting on the research assignment process (e.g. what the candidate has learnt from undertaking research). |

| Criterion 7 | 8 – 10 | 5 - 7 | 3 – 4 | 0 – 2 |

| Acknowledgement of sources (10 marks) | Shows thorough/ excellent understanding of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows adequate understanding of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows some evidence of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). | Shows little or no evidence of acknowledging sources (e.g. footnotes, references, plagiarism). |

TOTAL = 85/100

NAME OF LEARNER:_____________________________________

GRADE: ________________________

FINAL MARK ALLOCATION

| Criteria | TOTAL MARKS | LEARNER’S MARKS |

Criterion 1 | 10 | 8 |

Criterion 2 | 20 | 18 |

Criterion 3 | 10 | 8 |

Criterion 4 | 30 | 25 |

Criterion 5 | 10 | 8 |

Criterion 6 | 10 | 8 |

Criterion 7 | 10 | 10 |

| TOTAL | 100 | 85 |

COMMENTS:

This is a well-researched and well-written piece of research – excellent work. You made a very good attempt to formulate and sustain a line of argument with regard to the key question. You used a variety of sources to substantiate the line of argument, which is excellent.

However, this research assignment could have been strengthened if relevant visual sources were used, at the appropriate points, to supplement your historical narrative. Finally, although you link back to the key question in places, you tend to focus on the separate struggles of women and not when they fought ‘side-by-side’ with men as stated in the question. I am glad that you enjoyed this research project. Well done!

TEACHER’S SIGNATURE:____________________________________

DATE: ___________________________________________________

7. GUIDELINES FOR LEARNERS AND TEACHERS:

EXEMPLAR RESPONSES: SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS

QUESTION 1

1.1

1.1.1 The apartheid government supported UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola) during the Angolan Civil War. ✔

1.1.2 Angolan economic installations targeted by the SA Defence force were the oil and railway and port installations; iron mines and electricity lines and factories.✔ ✔✔✔

1.1.3 The apartheid government felt threatened by the MPLA because it was multi-racial, therefore undermined the social and racial policies of apartheid. ✔✔ Secondly, it supported ANC training bases openly, thereby supporting the SA liberation groups which sought to destroy the apartheid regime, i.e. supported the enemies of the SA apartheid government✔✔. Thirdly, the MPLA supported SWAPO, the Namibian liberation group which was fighting the SA forces in South West Africa and seeking political liberation from the domination of SA✔✔

1.1.4 During the Angolan Civil War, the SA army invaded Angola in support of the UNITA (Pro-capitalist) rebel group which sought to overthrow the governing MPLA government. The SA army reached an area close to the capital and UNITA forces followed behind them, capturing towns where the SA forces had overthrown and defeated the local MPLA ruling groups. Therefore, the country was in danger of a total coup by the SA backed pro-capitalist UNITA forces. In this context, the MPLA government had no choice but to seek aid from the Communist bloc in order to stop the invasion of SA troops and the defeat of the MPLA by UNITA. ✔✔✔

1.2

1.2.1 The message conveyed by the cartoon is that the USSR, portrayed as SANTA in his sleigh, is generously supplying arms to the MPLA as SANTA generously brings presents at Christmas time. ✔✔ These weapons will be used to destroy the UNITA and FNLA forces in the Angolan civil war - as there is a pun on the word ‘sleigh’-it is written as ‘slay’, i.e. to kill✔✔.

1.2.2 It may, to a large extent, be regarded as biased as it comes from the cartoon archives of Great Britain, who supported capitalism and democracy during the Cold War era when the Angolan civil war took place ✔✔. It therefore portrays the USSR in a negative light as an ‘evil SANTA’ bringing weapons to cause death and destruction in its bid to spread communism in Africa in its support of African political groups. ✔✔

1.3

1.3.1 The Soviet Union ✔and Cuba✔

1.3.2 It is an economic system whereby the government controls all the means of production, where free enterprise is forbidden and individual freedom is less important than the interests of the community. ✔✔