HISTORY PAPER 1 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS SEPTEMBER 2016

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY

PAPER ONE (P1)

GRADE 12

NSC PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS

SEPTEMBER 2016

ADDENDUM

SECTION A: SOURCE-BASED QUESTIONS

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE BERLIN CRISIS INTENSIFY THE COLD WAR TENSIONS BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE SOVIET UNION IN THE 1960s?

SOURCE 1A

This source explains the reasons why the Soviet Union decided to build a wall to separate East Berlin from West Berlin.

The existence of West Berlin, a conspicuously (easily noticed) capitalist city deep within communist East Germany, ‘stuck like a bone in the Soviet throat,’ as Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev put it. The Russians began manoeuvring (attempting/trying) to drive the United States, Britain and France out of the city for good. In 1948, a Soviet blockade of West Berlin aimed to starve the western Allies out of the city. Instead of retreating, however, the United States and its allies supplied their sectors of the city from the air. This effort, known as the Berlin Airlift, lasted for more than a year and delivered more than 2,3 million tons of food, fuel and other goods to West Berlin. The Soviets called off the blockade in 1949. [From: www.history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-wall. Accessed on 29 October 2015.] |

SOURCE 1B

This source explains how the actual construction of the Berlin Wall increased tensions between the United States of America and the Soviet Union.

| In the early morning hours of 13 August 1961, temporary barriers were put up at the border separating the Soviet sector from West Berlin, and the asphalt (tar) and cobblestones on the connecting roads were ripped up. Police and transport police units, along with members of “workers’ militias,” stood guard and turned away all traffic at the sector boundaries. Over the next few days and weeks, the coils (rolls) of barbed wire strung along the border to West Berlin were replaced by a wall of concrete slabs and hollow blocks. This was built by East Berlin construction workers under the close scrutiny of GDR border guards. On 25 October 1961, American and Soviet tanks faced off against each other at the Friedrichstrasse border crossing used by foreign nationals (Checkpoint Charlie), because GDR border guards had attempted to check the identification of representatives of the Western Allies as they entered the Soviet sector. In the American view, the Allied right to move freely throughout all of Berlin had been violated. For sixteen hours, the two nuclear powers confronted each other from a distance of just a few meters, and the people of that era felt the imminent threat of war. The next day, both sides withdrew. Thanks to a diplomatic initiative by America's President Kennedy, the head of the Soviet government and communist party, Nikita Khrushchev, had confirmed the four-power status of all of Berlin, at least for now [Adapted from: www.berlin.de/mauer/geschichte/index.en.htm. Accessed on 1 November 2015.] |

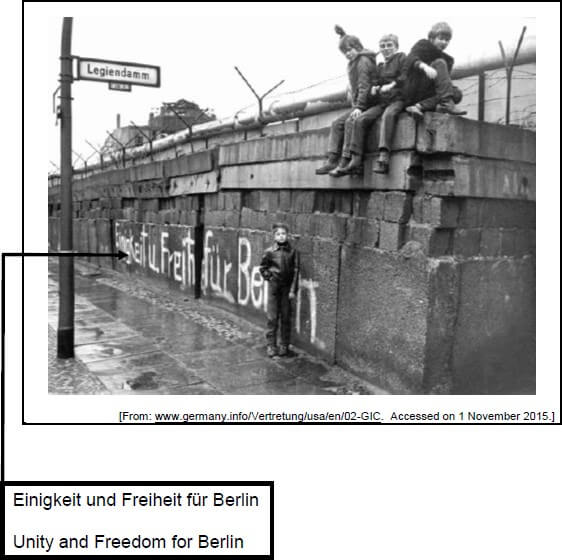

SOURCE 1C

This visual source depicts children playing on top of the Berlin Wall in the West Berlin district of Kreuzberg in March 1972.

SOURCE 1D

This is an extract from a speech by President Kennedy of the United States of America. He responded to the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 at the Rudolph Wilde Platz in Berlin.

… We cannot and will not permit the Communists to drive us out of Berlin, either gradually or by force. For the fulfilment of our pledge to that city is essential to the morale and security of Western Germany, to the unity of Western Europe, and to the faith of the entire Free World. [From: www.history.com/topics/berlin-wall. Accessed on 30 October 2015.] |

QUESTION 2: WHAT IMPACT DID THE INVOLVEMENT OF FOREIGN POWERS HAVE ON THE ANGOLAN CIVIL WAR?

SOURCE 2A

This source outlines the involvement of foreign countries in the Angolan conflict.

| The South African invasion, Cuban intervention and Soviet and American assistance internationalised the Angolan conflict. Although the FNLA ceased to exist in 1976, UNITA – benefiting from the extensive South African military assistance as well as United States aid and a lucrative (profitable) diamond smuggling industry – built a formidable fighting force of around 40 000 soldiers. For nearly two decades a civil war raged between UNITA guerrillas and the MPLA government, killing more than 1,1 million civilians, mostly in the rural areas, where over eighty percent of the population lives. The MPLA, a Marxist-Leninist party since 1977, expanded educational opportunities and the health care system and nationalised industries deserted by Portuguese settlers and foreign corporations. But its state owned farms and inefficient bureaucracies (administrative staff) only made life more difficult in the countryside, where roads deteriorated and small farmers were left without access to markets or agricultural inputs … President Neto and Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who succeeded Neto in 1979, pursued pragmatic economic policies, permitting private ownership and co-operating with Western oil companies in exploiting Angola’s rich oil reserves off the coast of the Cabinda enclave (an area totally surrounded by the territory of another country)… Much – if not all – of the $400 million annual oil revenues were spent on the war effort … [From: Africana: The Encyclopaedia of the African and African American Experience, edited by KA Appiah and HL Gates Jr.] |

SOURCE 2B

The extract below explains the reasons for the involvement of the United States of America in the Angolan conflict. It focuses on the USA’s attempts to recover from the embarrassment of Vietnam.

The USA wanted to prevent a Soviet backed communist government from coming to power in Angola. For this reason, it supplied weapons, funding and supplies both the FNLA and UNITA. This was stepped up after the American withdrawal from Vietnam. The American government was keen to assert its position in Africa after its humiliating defeat by the communists in Vietnam. They saw this as a way of restoring the balance of power between the superpowers. However, after its defeat in Vietnam, the USA was not prepared to become directly involved in the fighting by sending troops. They secretly encouraged the invasion by the South African Army, hoping that this would prevent the MPLA from coming to power. The effect of US involvement was to prolong the civil war. [From: In Search of History by J Bottaro et al] |

SOURCE 2C

This source compares two schools of thought, a Cuban and South African viewpoint on the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale.

| One school of thought (supported by the ANC, Cuba, other liberation movements and several historians) is that South Africa’s decision to launch the attack was influenced by their intention to rescue UNITA and their want to seize the town of Cuito Cuanavale through the capture of the air force base. It is argued that the actions of the SADF prior to the 23 March 1988 are clear evidence of their determination to break-through to the town. The SADF forces attacked Cuito with the massive 155 mm G-5 guns and staged attack after attack led by the crack 61st mechanised battalion, 32 Buffalo battalion, and later 4th SA Infantry group. On the 23rd March the battle reached a halt. In the words of 32 Battalion commander, Colonel Jan Breytenbach. He writes: ‘the UNITA soldiers did a lot of dying that day’ and ‘the full weight of FAPLA’s defensive fire was brought down on the heads of [SADF] Regiment President Steyn and the already bleeding UNITA.’ According to this view, the SADF failed in its intention and was successfully thwarted by the combined Angolan forces. The second school of thought maintains that the SADF had only limited objectives, namely, to halt the enemy at Cuito, to prevent its airstrip from being used, and then to retreat. Further action would have undermined negotiations between Cuba, Angola and South Africa, which began in London early in 1988 and continued in May in Brazzaville, Congo, and Cairo, Egypt. By this time, the South African government had already recognised the political change in Russia and the ending of the cold war. Gen. Jannie Geldenhuys, Chief of the SADF, stated that the most important battle in the campaign was when the Cubans were defeated at the Lomba River and Cuito Cuanavale was simply part of a mopping up operation after this battle. Following this the SADF’s intention was to prevent the capture of Mavinga and through that prevent assaults on Jamba. This was successfully accomplished. This view is supported by the SADF and several historians such as Fred Bridgeland, W.M. James and others. In addition both SADF and military analyst’s statistics are mentioned contradicting claims of a victory. Gen. Jannie Geldenhuys, Chief of the SADF, quoted the following in support of this argument: CUBA/FAPLA Tanks destroyed: 94, SADF tanks destroyed: 3, Cuban troop carriers destroyed: 100, SADF troop carriers destroyed: 5 logistical vehicles destroyed: 389 for Cuba and 1 for SADF. [From:www.sahistory.org.za/tops/battle-cuito-cuanavale. Accessed on 26 October 2015.] |

SOURCE 2D

This photograph shows the South African Defence Force recruits making their weapons safe before entering the base at Ruacana in 1988 during the Battle of Cuito Cuanavale. It is adapted from a newspaper article, The Mother of Liberation Battles.

[Source: The Mother of Liberation Battles’, an article by Ronnie Kasrils, From: Sunday Independent, 24 March 2013] |

QUESTION 3: HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE DESEGREGATION OF CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL IN LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS, IN 1957?

SOURCE 3A

The source below is an extract taken from notes by President Dwight Eisenhower on 8 October 1957 after his meeting with Governor Faubus. It focuses on the visit of Governor Faubus of Arkansas to Little Rock on 14 September 1957. The meeting took place in Newport.

| Governor Faubus protested again and again that he was a law abiding citizen, that he was a veteran, fought in the war, and that everybody recognises that the Federal law is supreme to State law. So I suggested to him that he go home and not necessarily withdraw the National Guard troops, but just change their orders to say that having been assured that there was no attempt to do anything except to obey the Courts and that the Federal government was not trying to do anything that had not been already agreed to by the School Board and directed by the Courts; that he should tell the Guard to continue to preserve order but to allow the Negro children to attend Central High School. I pointed out at that time he was due to appear the following Friday, the 20th, before the Court to determine whether an injunction (compelling court order) was to be issued … I further said that I did not believe it was to anybody to have a trial of strength between the President and a Governor because in any area where the Federal government had assumed jurisdiction (authority) and this was upheld by the Supreme Court, there could be only one outcome … that is, the State would lose, and I did not want to see any Governor humiliated. [From: www.mhunt.weebly.com. Accessed on 13 November 2015.] |

SOURCE 3B

This is a statement by the Governor of Arkansas, Orval Faubus, after his meeting with President Dwight Eisenhower in September 1957. It outlines the incident at Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

| … I have assured the President on my desire to cooperate with him in carrying out the duties resting upon both of us under the Federal Constitution. In addition, I must harmonise (bring in line with) my actions under the Constitution of Arkansas with the requirements of the Constitution of the United States. I have never expressed any personal opinion regarding the Supreme Court decision of 1954 [Brown v Board of Education] which ordered integration. This is not relevant. That decision is the law of the land and must be obeyed. At the same time it is evident from the language of the decision itself that changes necessitated by the Court orders cannot be accomplished overnight. The people of Little Rock are law-abiding and I know that they expect to obey valid court orders. In this they shall have my support. [From: www.ourdocuments.gov. Accessed on 14 November 2015.] |

SOURCE 3C

This extract describes the hardships that the African American students, who attended the ‘all-white’ Central High School. It also focuses on how their families were harassed.

Although some of the students, teachers and administration attempted to maintain a sense of normality, for the nine students that integrated Central High School it was like going to war every day. One of the Little Rock Nine, Melba Pattilo Beals, describes their experience in her book, Warriors Don’t Cry: ‘My eight friends and I paid for the integration of Central High with our innocence. During those years when we desperately needed approval from our peers, we were victims of the harshest rejection imaginable. The physical and psychological punishment we endured profoundly affected our lives. It transformed us into warriors who dared not cry even when we suffered intolerable pain.’ [From: www.nps.gov/history/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons . Accessed on 14 November 2015.] |

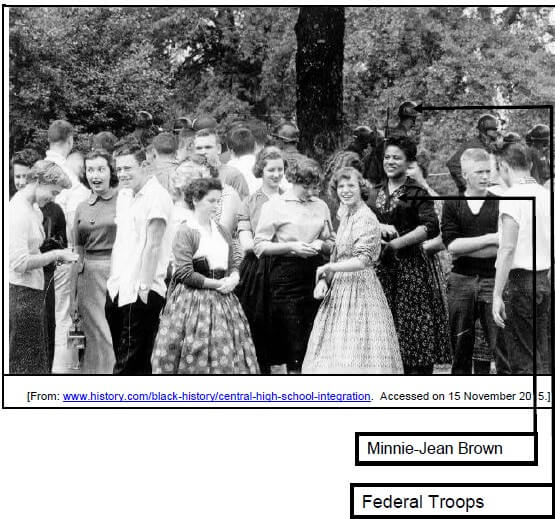

SOURCE 3D

This photograph shows some African and White American students interacting at Central High School in 1957.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

- Appiah, KA and Gates, HL Jr (Editors), Africana: The Encyclopaedia of African and African American Experience (Oxford University Press)

- Bottaro J et al, 2013, In Search of History (Oxford University Press)

- Kasrils R, “The Mother of Liberation Battles”Sunday Independent, March 24, 2013 www.berlin.de/mauer/geschichte/index.en.htm

- www.germany.info/Vertretung/usa/en/02-GIC

- www.germany.infor/Vertreting/usa/en/02-GIC

- www.history.com/black-history/central-high-school-integration

- www.history.com/topics/cold-war/berlin-wall

- www.sahistory.org.za/tops/battle-cuito-cuanavale

- www.mhunt.weebly.com

- www.nps.gov/history/nr/twhp/wwwlps/lessons

- www.ourdocuments.gov