History Paper 2 Addendum - Grade 12 September 2021 Preparatory Exams

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: WHAT WERE THE CHALLENGES THAT THE SOUTH AFRICAN GOVERNMENT FACED DURING THE 1980s?

SOURCE 1A

This source below explains why there was increased resistance to apartheid in the 1980s.

After the Soweto Uprising of 1976, the South African government led by P.W. Botha, introduced changes which it claimed were reforms, called the ‘Total Strategy’. Botha also realised the strength of united black resistance. The National Party (NP) government had initially used a ‘divide and rule’ approach by dividing the population into ethnic (Xhosa, Zulu, etc) groups and by treating each other differently. This division was however failing and the resistance against apartheid becoming more and more united. The government therefore tried to find new ways of dividing the population. Its strategy was to admit a small and carefully chosen and controlled number of black people into the middle class. The thinking was that, by creating a richer, black middle class, who would support apartheid and the government because they now needed apartheid to keep their elevated (higher) positions, black resistance would be reduced. In 1982 P.W. Botha’s government passed the Urban Bantu Authorities Act which was an attempt to give more power to black local councillors in the townships. The government also tried to make the gap between Coloured, Indian and African more defined. This was done through the new constitution that the NP introduced in 1983. The constitution created a new parliamentary system, called the Tricameral Parliament. Botha’s government suggested that political power in South Africa be shared among Whites, Coloureds and Indians, with separate houses of parliament to be established for each racial group. The new constitution came into force in 1984, comprising of one hundred and seventy-eight (178) members (all white) House of Assembly, an eighty-five [From www.sahistory.org.za>article>apartheid-era-1980s. Accessed on 12 February 2021.] |

SOURCE 1B

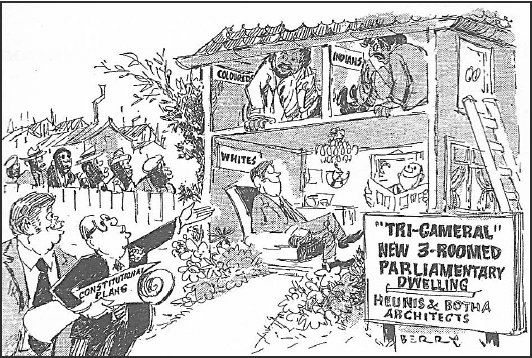

This cartoon below depicts the creation of the Tri-cameral Parliament by the new constitution of 1983.

[From sahistory.org.za. Accessed on 12 February 2021].

SOURCE 1C

This source below describes the reaction of the United Democratic Front (UDF) towards the reforms implemented by the apartheid government in the 1980s.

One of the reasons why the 1980s became so violent and moved South Africa towards change was because the opposition to apartheid became united. There was mass action from the people, and although they were all part of different community groups, they acted together for the same aim. A very important organisation during the 1980s was the United Democratic Front (UDF). It was established in response to a call by Dr Allan Boesak at a meeting of the Transvaal Anti-South African Indian Council’s Congress. He suggested that all opposition to the 1983 constitution should be united, or as he put it, “the politics of refusal needed a united front.” The UDF was launched nationally at a meeting in Mitchell’s Plain on 20 August 1983. It consisted of hundreds of women, students, churches, trade unions, cultural, sporting and other groups. At the launch Dr Allan Boesak stated in his speech, “We want all our rights, we want it here and we want it now.” In the period from 1983 to 1989 the UDF established itself as one of the most prominent political movements in South Africa with more than 600 affiliated organisations. They decided on a logo and a slogan, ‘UDF Unites, Apartheid Divides.’ The UDF was quite successful in their initial ‘Don’t Vote’ campaign for the Tri- cameral Parliament, and voter turn-out at the elections was very low. In January 1984 it launched the ‘Million Signatures Campaign’ against apartheid. After its formation, the UDF declared it wanted to establish a true democracy in which all South Africans could participate and create a single, non-racial, unfragmented (undivided) South Africa. [From www.globalsecurity.org>world>war>south-africa5.htm. Accessed on 12 February 2021.] |

SOURCE 1D

This source explains the rent boycotts embarked on by civil society in the township of Mamelodi in 1986.

Evidence that political consciousness in the townships had become increasingly combative (aggressive) emerged during 1986 when the rent boycott spread to 54 townships countrywide. This involved about 300 000 households and cost the state at least R40 million per month. The rent boycotts were a response to both economic and political grievances. Economic grievances involved the level and quality of urban subsistence (survival): declining real wages as inflation increased the cost of basic foodstuff and transport by 20%, overcrowding with a national average of 12 people per household, massive housing shortages, rising rent and service charges (sometimes by 100%) and growing unemployment. Political grievances were linked to state failure to give blacks political rights in general and the persistent inadequacy and illegitimacy of the black local authorities in particular. Therefore, residents attacked and burned government buildings and sought to destroy all elements of the apartheid administration. Numerous attacks were made on the homes of black policemen and town councillors. An August 1986 UDF information pamphlet pointed out that rent was not being paid because ‘people are simply unable to afford it. The rent boycott is … part of an attempt to make apartheid unworkable.’ The rent boycott weakens the structures of the government and demonstrates that there can be no taxation without representation. Unlike consumer boycotts, which aimed at pressurising the state through the middle class white commercial interest, rent boycotts challenge the state directly. President Botha activated security legislation to deal with these crises. In mid-1985 he imposed the first in a series of state of emergencies in various troubled parts of South Africa. [From https://markswilling.co.za/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/ UNITED- DEMOCRATIC-FRONT-AND- TOWNSHIP-REVOLT.pdf. Accessed on 12 February 2021.] |

QUESTION 2: DID THE AMNESTY PROCESS OF THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) BRING CLOSURE TO THE FAMILY OF DR NEIL AGGETT?

SOURCE 2A

The source below explains the role that Dr. Neil Aggett played in the labour movement and the events that led to his death.

Neil Aggett, the first white South African who died in detention during apartheid was born in Kenya. Aggett’s family moved to South Africa in 1964. Aggett became a medical doctor. His internship at the Mthatha General Hospital and in Tembisa, which were located in poor “black areas”, contributed to his social consciousness. He witnessed the extreme poverty and diseases affecting black workers in these overcrowded, poorly resourced hospitals. This would lead to his involvement in the trade union movement, where he became famous for fighting the cause of workers in the African Food and Canning Worker’s Union. Aggett was arrested for his involvement in the labour movement under the Terrorism Act. He was taken to John Vorster Square, where he was repeatedly interrogated, beaten and tortured by the Special Branch officers, which labelled (regarded) him as a communist. On 5 February 1982, Aggett hanged himself with a scarf. Aggett became the 51st person to die in police detention. At least 15 000 attended his funeral, and his death sparked widespread protests and strikes. [From www.news24.com>news24>southafrica>news>explained-who-was-neil-aggett-and-why-he- importantimportant-20200122. Accessed on 4 February 2021.] |

SOURCE 2B

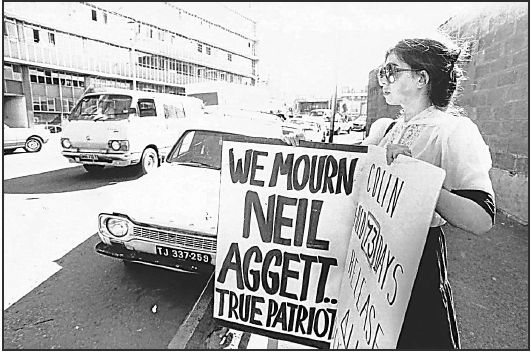

This photograph shows a supporter mourning the death of Neil Aggett that took place on 13 February 1982.

[From https:www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-02-04-remembering-neil-aggett-the-modest-idealist- who-died-for-his-beliefs-39- years-ago. Accessed on 12 July 2021.]

SOURCE 2C

The source below focuses on the reopening of the inquest into the circumstances that led to the murder of Neil Aggett.

Nearly four decades later, the reopening of the inquest into the death in detention of Neil Aggett may finally yield answers and truth. An inquest cleared the apartheid police, security branch officers, of wrongdoing. They called Aggett’s death a suicide. His friends and family have never believed it. Family, friends and a team of supporters, including human rights lawyers, have challenged the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) since 2003 to have Aggett’s case and those of other activists be reinvestigated. Security Branch policemen, Lieutenant Steven Whitehead and Major Arthur Conwright, who were identified as Aggett’s chief torturers, have died. However, former security branch police officer Nick Deetlefs, who was among the interrogators accused of torturing political activists, was concluding his testimony at the reopened inquest into the death of anti- apartheid activist Dr Neil Aggett. He admitted that he had lied in the previous Aggett inquest, which included concealing his claim that Aggett had said that he did not want to live anymore. Deetlefs accused the security branch of having instructed him to lie about their operations, adding that he had decided that he would tell the truth after legal ‘There is no one that is intimidating (threatening) me now or telling me what to say. My legal representatives told me and warned me that I should tell the truth’. Deetlefs had initially told the court that torture of political detainees was routine practice at the notorious 10th floor of John Vorster Square Police Station, but said he did not know who was responsible for the torture after being asked to name the security officers who assaulted detainees. Aggett’s family representative indicated their intention to pursue criminal prosecution against Deetlefs as they accused him of covering up the torture and murder of Aggett. [From https://www.iol.co.za/news/politics/neil-aggett-inquest-blow-to-deetlefs-credibility-43044277. Accessed on 24 February 2020.] |

SOURCE 2D

The following extract describes an interview by former TRC commissioner, Yasmin Sooka that was held with Jill Burger, Neil Aggett’s sister, at the Johannesburg High Court on 20 January 2020. This was at the second inquest of how his death affected their family.

Many security police, including Cronwright and Whitehead, did not apply for amnesty at the TRC. Therefore, there has been a sustained attempt by activists, the family and the Neil Aggett support group to lobby (push) for the post-apartheid state to pursue Aggett’s torturers. Former TRC commissioner, Yasmin Sooka, says the opening of the inquest marks an important moment for Aggett’s family and many other families to learn about what really happened to those that were brutally tortured by the security police. Sooka said the family is determined to get to the bottom of what happened, but that many former apartheid police officers – some of whom were in command structures – have been regrouping “to prevent any information emerging around things that implicate them”. Jill Burger told the court the family always believed that Neil did not commit suicide, despite a 1982 ruling that cleared the police of any wrongdoing. “He would have never committed suicide. He was a strong man. I believe that the police officers either staged his death, or he committed suicide as a result of the brutal treatment he received. They killed him.” Although Aggett’s socialist views had led to clashes with his less politically aware father, Burger said her father had been distraught about his youngest son’s death. “My father could not stop weeping. He was a broken man,” she told the court. She said her father’s dying wish was that his son’s killers be brought to book. She added that some of her late father’s conservative friends had been under the impression that Neil ‘had got what he deserved’. “My father never spoke to those people again.” “I do still get sad and teary because he was living such a useful life. He had so much more to contribute and we’ve all missed out.” She further continued to say “my wish is that he is at peace and that my mother and father are at peace. My poor loving mother, I’m glad she didn’t live to hear the things that are coming out of the inquest.” [From https:www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-02-04-remembering-neil-aggett-the-modest-idealist-who-died-for-his-beliefs-39-years-ago. Accessed on 4 February 2021.] |

QUESTION 3: WHAT IMPACT DID THE GLOBAL COVID-19 PANDEMIC HAVE ON SOUTH AFRICA?

SOURCE 3A

This source explains the origin of the Covid-19 pandemic and its intended impact on South Africa.

COVID-19 was first identified in the Hubei Province, City of Wuhan, China in the latter part of 2019. Soon after, this disease began to wreak havoc (chaos) and the devastating (harmful) effect of the pandemic forced the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare it as a global pandemic. In South Africa, the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was recorded on 5 March 2020. The fear of the predicted rate at which the pandemic was to infect people motivated the South African government to declare this pandemic a national state of disaster in terms of the Disaster Management Act. The national state of disaster declared on 15 March 2020 by the President of South Africa Cyril Ramaphosa initially contained partial travel bans, travel advisories, discouraging public transport, the closing of schools, and prohibiting gatherings of more than 100 people. Subsequently, on 23 March 2020, President Ramaphosa instituted a national lockdown that would last for 21 days from 26 March 2020 to 16 April 2020. The lockdown meant that among other organisations that would immediately close were schools and all institutions of higher learning. On 9 April 2020, the President of South Africa announced that the lockdown would be extended by a further 14 days. With the national lockdown, it would mean that the academic calendar for the year 2020 would be affected. To reduce the extent of academic disruptions, several learning institutions responded by moving some of the courses to their online platforms. For basic education, some Non-Governmental Organisations made learning materials available. |

SOURCE 3B

The source below describes the social impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on South Africa.

COVID-19 has shown its potential devastating (damaging) impact elsewhere, but it is a particular cause for concern in South Africa. While public health strategies such as social distancing, wearing of masks and regular handwashing are encouraged, such strategies are a privilege as many cannot afford it in the overcrowded, informal settlements that is 13% of all households, where many don’t have access to running water. The health systems in high income countries are being stretched, but in South Africa most people rely on the public health system that is under-resourced and is struggling to meet the demands of the pandemic. While the virus does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex or borders, it is likely to affect the poor and those suffering from other comorbidities (multiple illnesses). President Cyril Ramaphosa stated that ‘urgent and drastic’ measures were necessary to limit the spread of the virus. A State of Disaster was declared by the President on 15 March 2020, thereby limiting certain rights and freedoms within South Africa. At the time of the announcements South Africa had the highest number of cases in Africa. The restrictions introduced were the most stringent (strict) in Africa, as South Africa was then the only country on the African continent to require all of its citizens to remain at home. The measures announced on 15 March and 26 March represents the most comprehensive limitations on the freedom of movement and assembly of all South Africa since apartheid. A failure to adhere to these regulations may result in a fine or imprisonment of six months or more. The leaving of a residence is only permitted to buy essential goods, seek medical attention, buy medical products, collect social grants or attend a funeral of no more than 50 people. [From https:/www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/sa-shares-coronavirus-experiences-bricks. Accessed on 25 January 2021.] |

SOURCE 3C

The source below describes the economic effects that the COVID-19 pandemic had on South Africa.

The economic sectors most disadvantaged include textiles, educational services, catering and accommodation (including tourism), beverages, tobacco, glass products and footwear. As of midnight on 26 March 2020, only essential goods may be sold. This includes any food and animal food products and hygiene products, medical and hospital supplies, fuel, coal, gas and basic goods, including airtime and electricity. The selling of alcohol and cigarettes were prohibited. Price controls on certain goods have also been introduced, including toilet paper, hand sanitiser and some food products. Failure to comply can result in a fine or imprisonment of up to six months. The economy was severely hit as most of the sectors faced a decrease in their productivity due to the lockdown. Workers were laid-off and unemployment rose. The Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fell from 5,1 and up to 7,9 percent in 2020. Given the decrease on household income there will be a decrease in household consumption, which will further fuel the decrease in production. This reduced household income will also lead to increased poverty, especially among the already vulnerable (helpless). [From https://reliefweb.int>reportand covid-19-south-afri-so ca … Accessed on 07 July 2021.] |

SOURCE 3D

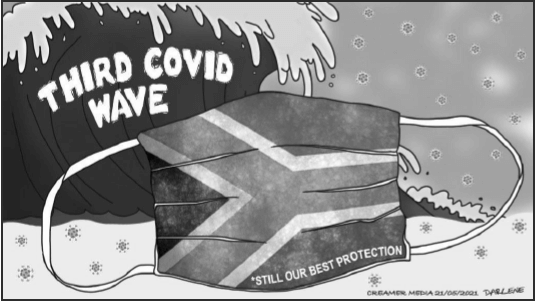

This cartoon depicts the Third Covid Wave affecting South Africa and the need to protect South Africans.

[From Mining Cartoons MiningWiikly.com. Accessed on 8 July 2021.]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

- https:www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-02-04-remembering-neil-aggett-the- modest-idealist-who-died-for-his-beliefs-39- years-ago

- http://indianexpress.com/aricle/explained/coronavirus-india/lockdown-migrant- workers-mass-exodus-6348834/

- https://sabctrc.saha.org.za/reports/volume3/chapter6/subsection24.html

- https:/www.sanews.gov.za/south-africa/sa-shares-coronavirus-experiences-bricks

- https://thewire.in/world/bricks-and-covid-rising-powers-in-a-time-of-pandemic

- Mining Cartoons MiningWiikly.com …

- sahistory.org.za

- Times Live 7/2/2021 www.globalsecurity.org>world>war>south-africa5.htm

- www.news24.com>news24>southafrica>news>explained-who-was-neil-aggett-and- why-he-was-important-20200122

- www.sahistory.org.za>article>apartheid-era-1980’s