HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - NSC EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2019

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY

PAPER 2

GRADE 12

NSC EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS JUNE 2019

ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: HOW DID THE DIFFERENT YOUTH ORGANISATIONS AND LEADERS INFLUENCE THE SOUTH AFRICAN YOUTH IN THE 1970s?

SOURCE 1A

This extract focuses on the roots of Black Consciousness.

The term Black Consciousness stems from American educator Du Bois’s evaluation of the double consciousness of American blacks being taught what they feel inside to be lies about the weakness and cowardice of their race. Du Bois insisted that black people take pride in their blackness as an important step in their personal liberation. [From Footprints in the Sands of Time by the Department of Education] |

SOURCE 1B

The extract below outlines how the South African Student’s Organisation (SASO) mobilised the black South African youth against the apartheid regime in the 1970s.

On one of the programmes that left the BCM's most enduring legacy, Ramphele wrote: ‘The programme for leadership development involved several levels of training and was undertaken as a joint venture by the SASO and BPC ... Weekend “formation schools” were held to train university students in various skills. In addition, an extensive training programme for youth leadership was undertaken to address the needs of high-school and township-based youth clubs in all the provinces of South Africa.’ [From The Road to Democracy in South Africa by M Mzamane et al] |

SOURCE 1C

The following source highlights the impact that the South African Students’ Movement (SASM) had on the youth of Soweto in 1976.

Sibongile Mkhabela, a leader of the South African Students’ Movement (SASM) at Naledi High, recalls that ‘there was serious mobilisation in the schools and this was done mainly through the SASM. SASM members were saying that this situation could not be allowed to continue. That was the build-up to the meeting on 13 June’. [From Soweto, A History by P Bonner and L Segal] |

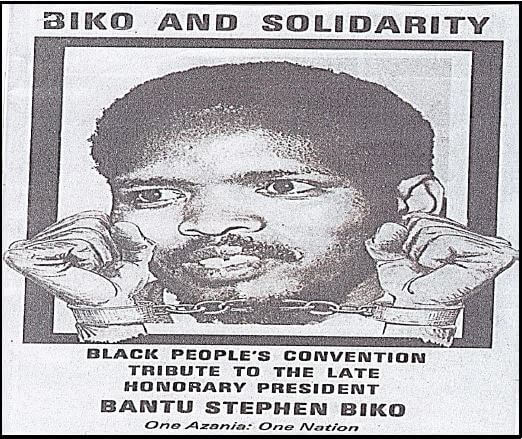

SOURCE 1D

The following poster was created to pay tribute to Biko after his death in 1977.

[From Steve Biko by M. Westcott]

QUESTION 2: HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) IN DEALING WITH SOUTH AFRICA’S DIVIDED PAST?

SOURCE 2A

This extract explains the reasons for the establishment of the TRC.

| After winning the 1994 elections, the ANC had a huge task of building a truly non racial and democratic South Africa, without forgetting its past. As Mandela stated, ‘There was no evil which has been so condemned (rejected) by the world as apartheid and therefore had to a find a way to forgive the perpetrators of the system of apartheid without forgetting the crimes against humanity’. The ANC’s solution to ‘forgiving without forgetting’ was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in 1996. The objectives of the TRC were to establish a complete picture as possible of the causes, nature and extent of the gross violation of human rights. It also had to facilitate the granting of amnesty to persons who made full disclosure of all the relevant facts related to acts of violence. The TRC was also charged with making known the fate of victims and restoring their human and civil dignity of such victims, by granting them the opportunity to tell their stories, by recommending reparation [From South Africa’s Transition to Democracy by S. Shaw] |

SOURCE 2B

This is a report of an interview that was conducted with Eugene de Kock after his first appearance before the TRC in September 1997.

De Kock had been an ‘implicated witness’ in the TRC hearing of five white former security policemen in Port Elizabeth who were applying for amnesty for the bombing … The ‘Motherwell Bombing’ was ordered by the commander of the police, General Nic van Rensburg, who had approached De Kock and asked him to ‘make a plan’ in silencing the Motherwell policemen. [From A Human Being Died That Night by P Gobodo-Madikizela] |

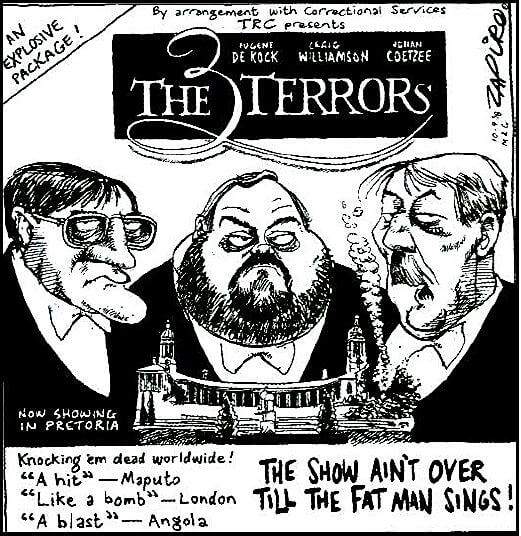

SOURCE 2C

This cartoon by Zapiro depicts Eugene de Kock, Craig Williamson and Johan Coetzee as ‘THE 3 TERRORS’ who were involved in the killing of many anti-apartheid activists.

[From Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: 10 Years On by Charles Villa-Vicencio et al]

SOURCE 2D

This extract by former President Thabo Mbeki focuses on the importance of telling the truth at the TRC hearings.

The great crevices (gaps) in our society which represented the absence of a national consensus about matters that are fundamental to the creation of the new society are also represented by the controversy which seems to have arisen around the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. [From The Life And Times Of Thabo Mbeki by A Hadland and J Rantao] |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Bonner P and Segal L. Soweto, A History

Department of Education, Footprints in the Sands of Time

Gobodo-Madikizela, P. A Human Being Died That Night

Hadland A. and Rantao J, The Life and Times of Thabo Mbeki

Mzamane M. et al, The Road to Democracy in South Africa

Shaw S, South Africa’s Transition to Democracy

Villa-Vicencio et al Truth and Reconciliation in South Africa: 10 Years On

Westcott M, Steve Biko