HISTORY PAPER 2 GRADE 12 ADDENDUM - AMENDED SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMS PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS MAY/JUNE 2018

Share via Whatsapp Join our WhatsApp Group Join our Telegram GroupHISTORY

PAPER 2

GRADE 12

AMENDED SENIOR CERTIFICATE EXAMS

PAST PAPERS AND MEMOS

MAY/JUNE 2018

ADDENDUM

QUESTION 1: WHAT IMPACT DID THE PHILOSOPHY OF BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS (BC) HAVE ON SOUTH AFRICANS IN THE 1970s?

SOURCE 1A

The source below outlines the philosophy of Black Consciousness and how it influenced the formation of the South African Students' Organisation (SASO).

According to Bantu Stephen Biko, 'Black Consciousness seeks to show the black people the value of their own standards and outlook. It urges black people to judge themselves according to these standards and not to be fooled by white society who have white-washed themselves and made white standards the yardstick (measure) by which even black people judge each other.' [From http:// www.sahistory.org.za/topic/defining-black-consciousness. Accessed on 8 February 2018.] |

SOURCE 1B

The review below is of a speech delivered by Anne Heffernen of Onkgopotse Tiro (member of SASO) at Turfloop University in 1972. It focuses on how members of SASO felt about Bantu Education.

… By the early 1970s, thanks to SASO's organisation on the campus, Turfloop was a hotbed (centre) of activism. Boycotts and protest marches became a regular feature of student life. In 1972 the rural campus came to national attention. At the university's graduation that year, Onkgopotse Tiro, a SASO member and former president of the SRC, gave a fiery (powerful) speech condemning Bantu Education and its implementation at Turfloop. Tiro attacked the fact that a supposedly black university was controlled by white leadership, that white companies received contracts to supply the campus and that white dignitaries took seats from black parents who came to see their children graduate. [From http://aidc.org/turfloop-soweto-back-dialectic-1976/. Accessed on 9 February 2018.] |

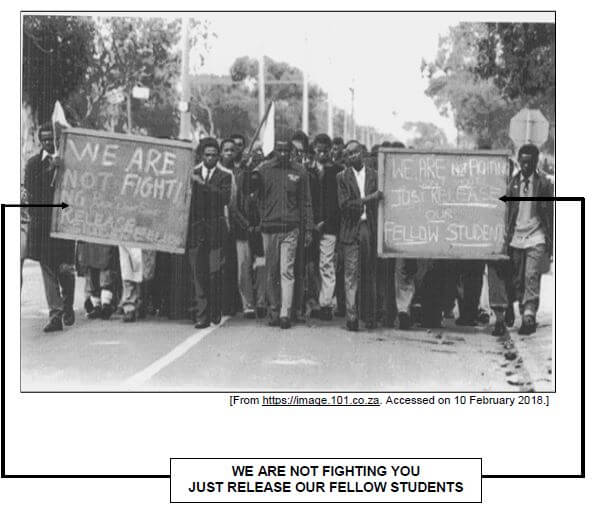

SOURCE 1C

The photograph below shows students marching and demanding the release of fellow students who were detained by the apartheid regime.

[From https://image.101.co.za. Accessed on 10 February 2018.]

SOURCE 1D

The extract below is a response by Bantu Stephen Biko on the success of the philosophy of Black Consciousness.

We have been successful to the extent that we have diminished the element of fear in the minds of black people. During the 1960s black people were terribly scared of involvement in politics. The universities were putting out no useful leadership to the black people because everybody found it more comfortable to lose themselves in a particular profession, to make money. But since those days, black students have seen their role as being primarily to prepare themselves for leadership roles in the various facets of the black community. Through our political articulation (expression) of the aspirations of black people, many black people have come to appreciate the need to stand up and be counted against the system. [From I Write What I Like: STEVE BIKO by A Stubbs ed.] |

QUESTION 2: HOW DID THE AMNESTY COMMITTEE OF THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC) DEAL WITH THE DEATH OF BANTU STEPHEN BIKO?

SOURCE 2A

The extract below focuses on the reasons for the formation of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was formed in 1995 to investigate human rights violations since 1960 and to grant amnesty to those perpetrators who made full disclosure. The commission also had to foster reconciliation and unity among South Africans. In exchange for full confessions of politically motivated crimes, the TRC promised amnesty for those who came forward. In 1997 the five former security officers who interrogated Steven Biko on 6 September 1967 applied for amnesty from the TRC. The TRC's mandate was to be even-handed, but its composition was hardly balanced. The chairman, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, was a patron of the United Democratic Front, the ANC's internal front since the early 1980s … [From Race and Reconciliation by D Herwitz] |

SOURCE 2B

The extract below is part of a statement that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission issued. It focuses on the application for amnesty by the five security policemen who were responsible for the killing of Bantu Stephen Biko.

In January 1997, a group of notorious (ruthless) security policemen from the regional headquarters in Port Elizabeth applied for amnesty for a string of murders in the Eastern Cape. For years their names had struck terror in the townships as they cruised (went) about acting with impunity (without approval). Now their only hope of avoiding prosecution was to testify before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. [From http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/pr/1999/p990216a.htm. Accessed on 9 December 2017.] |

SOURCE 2C

This source focuses on why amnesty was not granted to four security policemen responsible for the killing of Bantu Stephen Biko.

AMNESTY DECISION ON DEATH OF STEVE BIKO Four former officers of the security branch, who applied for amnesty for the murder of Black Consciousness leader Bantu Stephen Biko in September 1997, were this week refused amnesty by the Amnesty Committee of the TRC and their applications were dismissed.

[From http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/pr/1999/p990216a.htm. Accessed on 28 November 2017.] |

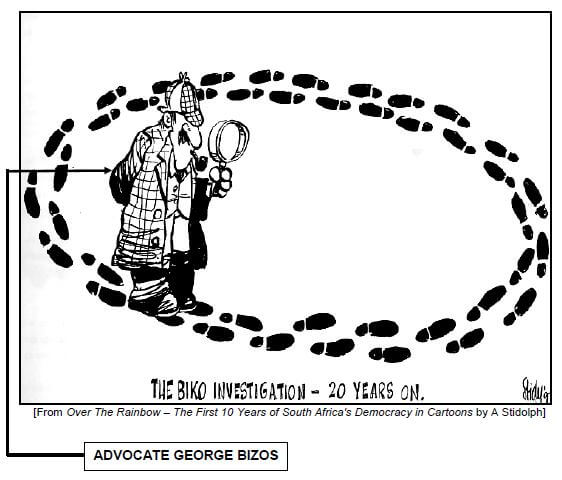

SOURCE 2D

The cartoon below by Stidy depicts the commemoration of the 20th anniversary of the killing of the Black Consciousness leader Bantu Stephen Biko. It appeared in Over The Rainbow – The First 10 Years of South Africa's Democracy in Cartoons and was produced on 12 September 1997.

QUESTION 3: HOW WAS SOUTH AFRICA'S CLOTHING AND TEXTILE INDUSTRY AFFECTED BY GLOBALISATION?

SOURCE 3A

The article below focuses on the impact that trade liberalisation had on the clothing and textile industry in South Africa. It was written by the Minister of Economic Development, E Patel, for The Journalist.

Before the transition (change) to democracy, the clothing and textile industry employed roughly 250 000 workers. It was supported by very high tariffs that kept foreign goods out, very low wages that kept costs down and substantial financial subsidies that kept businesses alive, particularly in the old homelands areas … which were not sustainable from the mid-1980s onwards. [From http://www.thejournalist.org.za/spotlight/unravelling-the-fabric-of-the-industry-south-africas clothing-and-textile-business. Accessed on 20 January 2018.] |

SOURCE 3B

The source below is a part of a transcript of an interview that E Vlok, the Director of Research, Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers' Union, gave on Cape Talk Radio on 6 April 2017. It outlines how globalisation impacted on South Africa's clothing and textile industry.

SOUTH AFRICAN CLOTHING AND TEXTILE INDUSTRY DROPS FROM 200 000 JOBS TO 19 000 Ettienne Vlok, Director of Research at the Southern African Clothing and Textile Workers' Union, spoke with Azania Mosaka about the challenges facing the textile industry. [From http://www.702.co.za/articles/251378/sa-clothing-and -textile-industry-drops-from-200-000-to 19-000-jobs-researcher. Accessed on 20 January 2018.] |

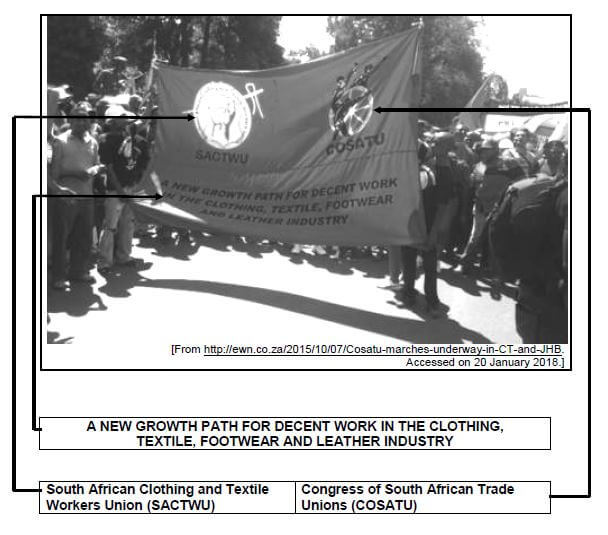

SOURCE 3C

The photograph below, by K Mogale, appeared on the web blog of Eye Witness News. It shows members of the Congress of South African Trade Union (COSATU) and the South African Clothing and Textile Workers Union (SACTWU) marching in Cape Town on 7 October 2017.

SOURCE 3D

This article focuses on the measures that the South African government took to bring about a turnaround in the clothing and textile industry. It appeared in the City Press on 11 October 2017.

The Minister in the Presidency for Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, Jeff Radebe, highlighted the clothing and textile industry as one of the sectors where the economy could most effectively be bolstered (boosted). [From https://www.fin24.com/Opinion/the-great-textile-turnaround-20171011. Accessed on 20 January 2018.] |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Visual sources and other historical evidence were taken from the following:

Herwitz D. 2003. Race and Reconciliation (University of Minnesota Press)

http://aidc.org/turfloop-soweto-back-dialectic-1976/

http://ewn.co.za/2015/10/07/Cosatu-marches-underway-in-CT-and-JHB

http://www.justice.gov.za/trc/media/pr/1999/p990216a.htm

http:// www.sahistory.org.za/topic/defining-black-consciousness

http://www.thejournalist.org.za/spotlight/unravelling-the-fabric-of-the-industry-south africas-clothing-and-textile-business

http://www.702.co.za/articles/251378/sa-clothing-and -textile-industry-drops-from-200- 000-to-19-000-jobs-researcher

https://image.101.co.za

https://www.fin24.com/Opinion/the-great-textile-turnaround-20171011

Stidolph A. 2003. Over The Rainbow – The First 10 years of South Africa's Democracy In Cartoons (Pietermaritzburg)

Stubbs A. (ed.) 2004. I Write What I Like: STEVE BIKO (Picador Africa)